Cloud Computing Review

Cloud computing allows companies to store their infrastructures remotely via the internet, ultimately reducing costs and creating value. We will go through a high level overview of cloud computing to prepare for the final exam.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Virtualization

- Containerization

- Distributed Storage Systems

- Distributed Computing Systems

Introduction

Cloud computing is a model for enabling ubiquitous, convenient, on-demand network access to a shared pool of configurable computing resources(e.g., networks, servers, storage, applications,and services) that can be rapidly provisioned and released withminimal management effort or service provider interaction.

- Ubiquitous: The ability to access computing resources from anywhere in the world.

- Convenient: The ability to access computing resources with minimal effort.

- On-demand: The ability to provision computing resources as needed.

Define by National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), U.S. Department of Commerce

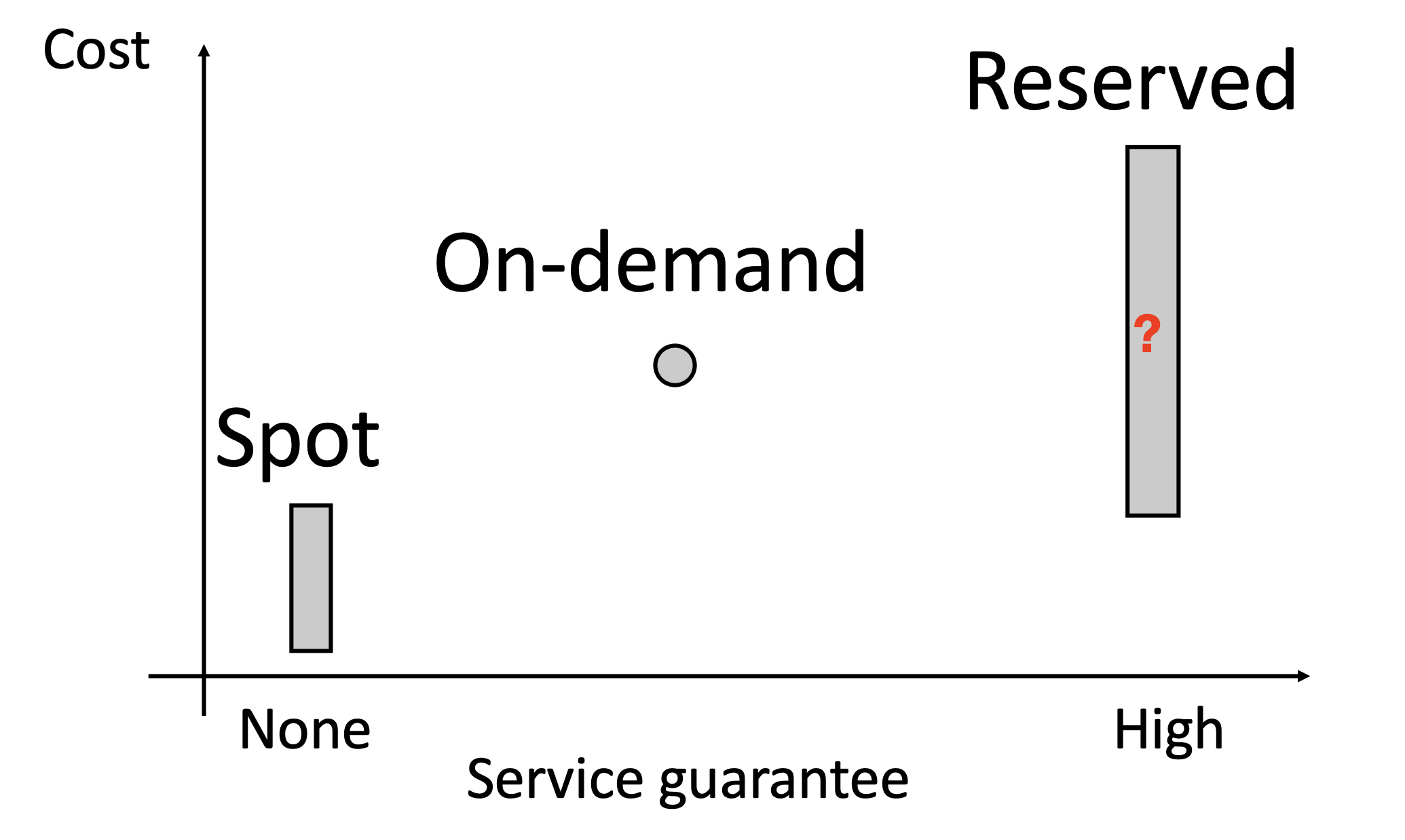

Cloud Pricing

Cloud Pricing refers to the pricing models and strategies adopted by cloud service providers for their services, such as computing, storage, and networking. Cloud pricing is typically based on a pay-as-you-go principle, meaning users pay only for the resources they actually consume. This approach enhances resource efficiency and reduces initial investment costs for users. Major pricing models include:

- Pay-as-You-Go: Users pay based on actual resource usage, often billed by the hour, minute, or second.

- Reserved Instances Pricing: Users commit to purchasing a certain amount of resources upfront (typically for one or more years) for discounted rates.

- Spot Pricing: A cloud pricing model where service providers offer their unused computing resources at prices lower than on-demand pricing, based on market supply and demand dynamics. This model is suitable for running flexible, fault-tolerant tasks, as services may be interrupted due to fluctuations in resource demand.

- Tiered Pricing: Unit prices decrease as usage increases. For instance, storage costs per TB decrease for data exceeding 1TB.

| Attribute | Pay-as-You-Go | Reserved Instances | Spot Pricing | Tiered Pricing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commitment | No | Yes | No | No |

| Pricing | Hourly/secondly | Upfront discount | Market-based | Unit price decrease with usage |

| Flexibility | High | Low to Medium | High | High |

| Interruptibility | Low | Low | High | Low |

| Cost Saving Potential | Standard | Significant (long-term) | Very High | Moderate to High |

| Use Cases | Temporary or unpredictable workloads | Stable, long-term workloads | Elastic, fault-tolerant tasks | Large-scale storage or data transfer |

Cloud Deployment Models

Cloud Deployment Models refer to the ways in which cloud computing resources are configured and utilized. Based on ownership, management, and access permissions, the primary deployment models are as follows:

- Public Cloud: Cloud services are provided by a third-party cloud provider and are available to all users.

- Private Cloud: Cloud resources are dedicated to a single organization and can be managed internally or by a third party.

- Hybrid Cloud: Combines public and private clouds to leverage the best of both, interconnected via technology like VPNs or dedicated networks.

- Community Cloud: Shared and managed by a group of organizations with common requirements (e.g., regulatory or compliance needs).

| Deployment Model | Characteristics | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Cloud | Operated by third-party providers, multi-tenant, pay-as-you-go, open to public | Low cost, high scalability, provider-managed | Higher security and privacy risks, limited customization |

| Private Cloud | Dedicated to a single organization, single-tenant, internally/externally managed | Enhanced security and privacy, high customization | High cost, limited scalability |

| Hybrid Cloud | Combines public and private clouds, interconnected via technology (e.g., VPN) | Balances cost and security, workload migration support | High management complexity, requires strong integration capabilities |

| Community Cloud | Shared by organizations with common needs (e.g., compliance), resource sharing | Cost/resource sharing, optimized for community needs | Limited flexibility and scalability, complex management |

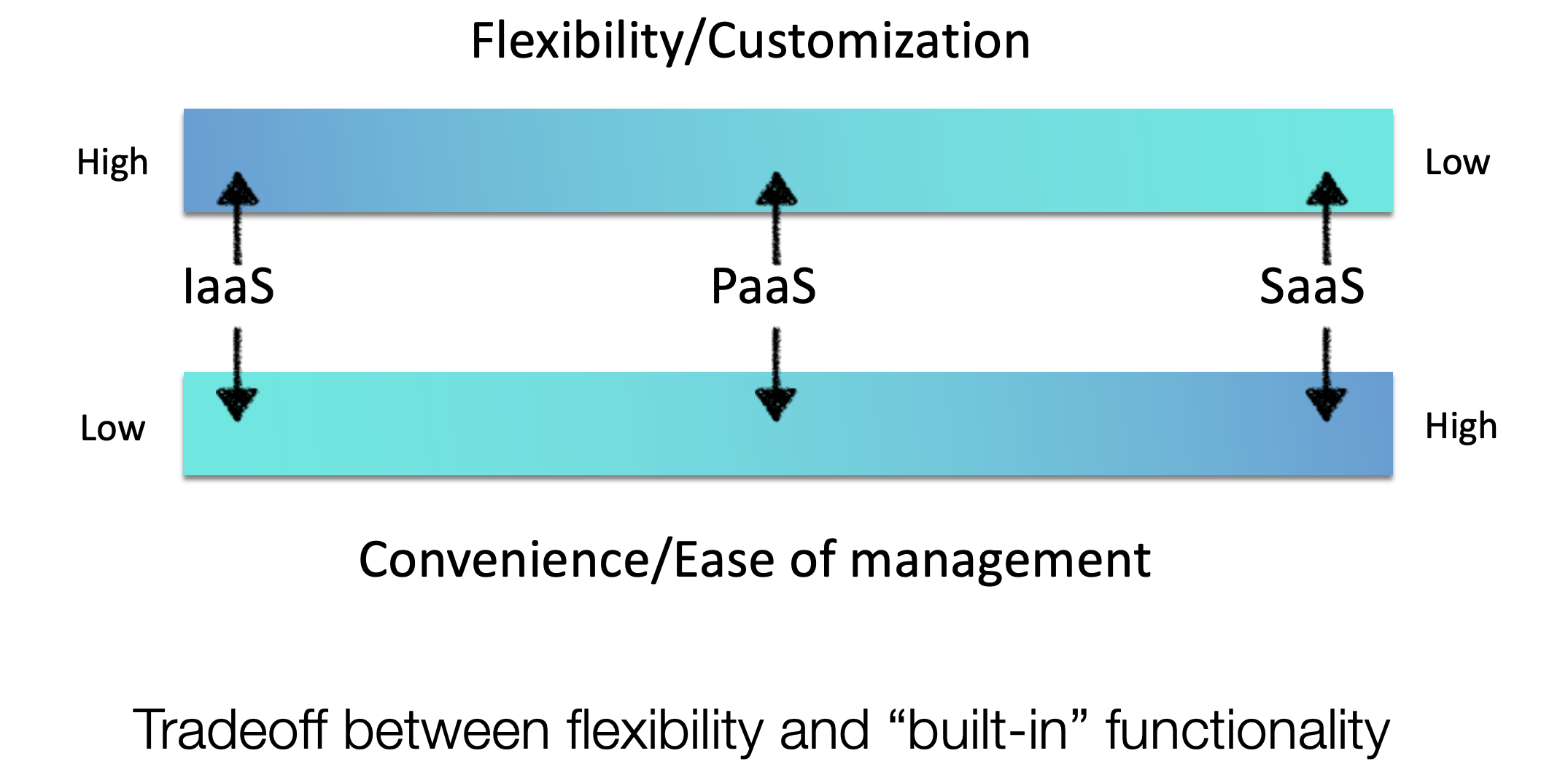

Cloud Service Models

Cloud service models are divided into multiple levels according to the level of abstraction and service types provided. The following are common models and their characteristics, advantages and applicable scenarios:

- Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS): Provides virtualized computing resources such as Virtual Machines (VMs), storage, and networking. Users can install any desired software on top of this infrastructure.

- Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS): In addition to infrastructure, it offers development tools, database management, Business Intelligence (BI) services, etc. It simplifies the process of developing and deploying applications.

- Software-as-a-Service (SaaS): Provides a complete software solution via a web browser or client, such as email, chat, and file sharing services.

- Function-as-a-Service (FaaS): A serverless architecture that allows developers to write and deploy individual functions or code snippets. These functions execute in response to triggers such as HTTP requests, database events, etc. The FaaS platform manages the servers and other infrastructure, allowing developers to focus on implementing business logic without worrying about the underlying resource configuration and management.

- Serverless Architecture: Doesn’t mean that there are literally no servers, but it means that developers don’t need to directly manage and maintain servers. All backend services are handled by the cloud provider.

- Trigger-based: Refers to events that can activate the execution of specific functions. For example, if a user uploads a picture to a storage bucket, this may trigger a function to automatically resize the picture.

- Machine Learning-as-a-Service (MLaaS): Provides a suite of tools and services that enable businesses and individuals to leverage machine learning technology without needing an in-depth understanding of its complex algorithms and technical details. MLaaS platforms typically offer data preprocessing, feature extraction, model training, evaluation, and prediction capabilities, with these operations often achievable through simple API calls. This service model significantly lowers the barrier to using machine learning technologies, promoting broader applications and development.

| Service Model | Characteristics | Advantages | Disadvantages | Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IaaS | Virtualized resources (VMs, storage, networking) | High flexibility, strong control, pay-as-you-go | Requires expertise, deployment complexity | Hosting, testing, data storage |

| PaaS | Development platform (OS, runtime, database, tools) | Efficient development, automated management | Low portability, limited customization | Web apps, APIs, microservices |

| SaaS | Complete software solutions via browser or client | No maintenance, multi-device access | Data privacy concerns, limited customizations | CRM, collaboration tools, email services |

| FaaS | Serverless model for running code | Low operational cost, elastic, precise billing | Cold start delay, complex state management | Event-driven tasks, IoT processing, APIs |

| MLaaS | Machine learning infrastructure and pre-trained models | Simplified MaaL deployment, cost-effective | Data privacy issues, limited model flexibility | Image recognition, NLP, predictive analytics |

| Other XaaS | Specialized services (e.g., storage, database) | Focused solutions, cost flexibility | Vendor dependence, management complexity | Database services, cloud storage |

FaaS and MLaaS are also referred to as Serverless. Serverless Architecture and Traditional Server-based Architecture differ significantly in several aspects, primarily including:

- Server Management: Core Differences

- Serverless Architecture: Developers do not manage any server hardware or operating systems. Cloud service providers take full responsibility for server configuration, security, and maintenance.

- Traditional Server-based Architecture: Developers must manage servers themselves, including installing operating systems, updating software, monitoring performance, and handling disaster recovery.

- Cost Structure:

- Serverless Architecture: Operates on a pay-as-you-go model where users only pay for the actual compute resources used. This model is especially suitable for applications with fluctuating traffic, as it can dynamically adjust resources based on need.

- Traditional Server-based Architecture: Typically involves fixed monthly or annual fees regardless of resource utilization. Over time, if resources are not fully utilized, it may lead to cost inefficiencies.

- Scalability:

- Serverless Architecture: Offers automatic scalability, increasing or decreasing instance numbers based on traffic changes to ensure the application always meets current demands.

- Traditional Server-based Architecture: While scalability can be automated, it often requires additional configuration and management and may not be as flexible as serverless architectures.

- Deployment Speed:

- Serverless Architecture: Reduces the time spent setting up environments, allowing new features to be deployed more quickly.

- Traditional Server-based Architecture: Requires more time to prepare and configure server environments, potentially delaying feature releases.

- Development Complexity:

- Serverless Architecture: Developers can focus on writing business logic code without worrying about underlying infrastructure issues.

- Traditional Server-based Architecture: Developers must consider effective server resource management and optimization alongside coding.

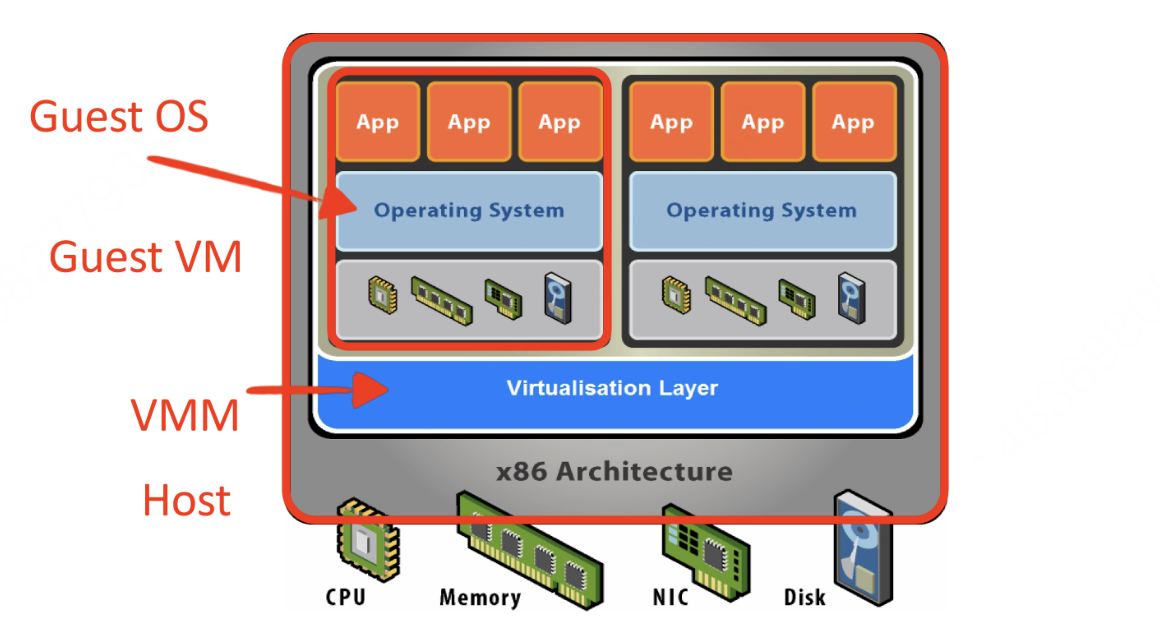

Virtualization

Virtualization technology is an important part of cloud computing and other IT infrastructure services. It allows us to create multiple virtual computing resources, such as servers, storage devices, and networks, which can run on a single physical hardware, thereby improving resource utilization and simplifying management.

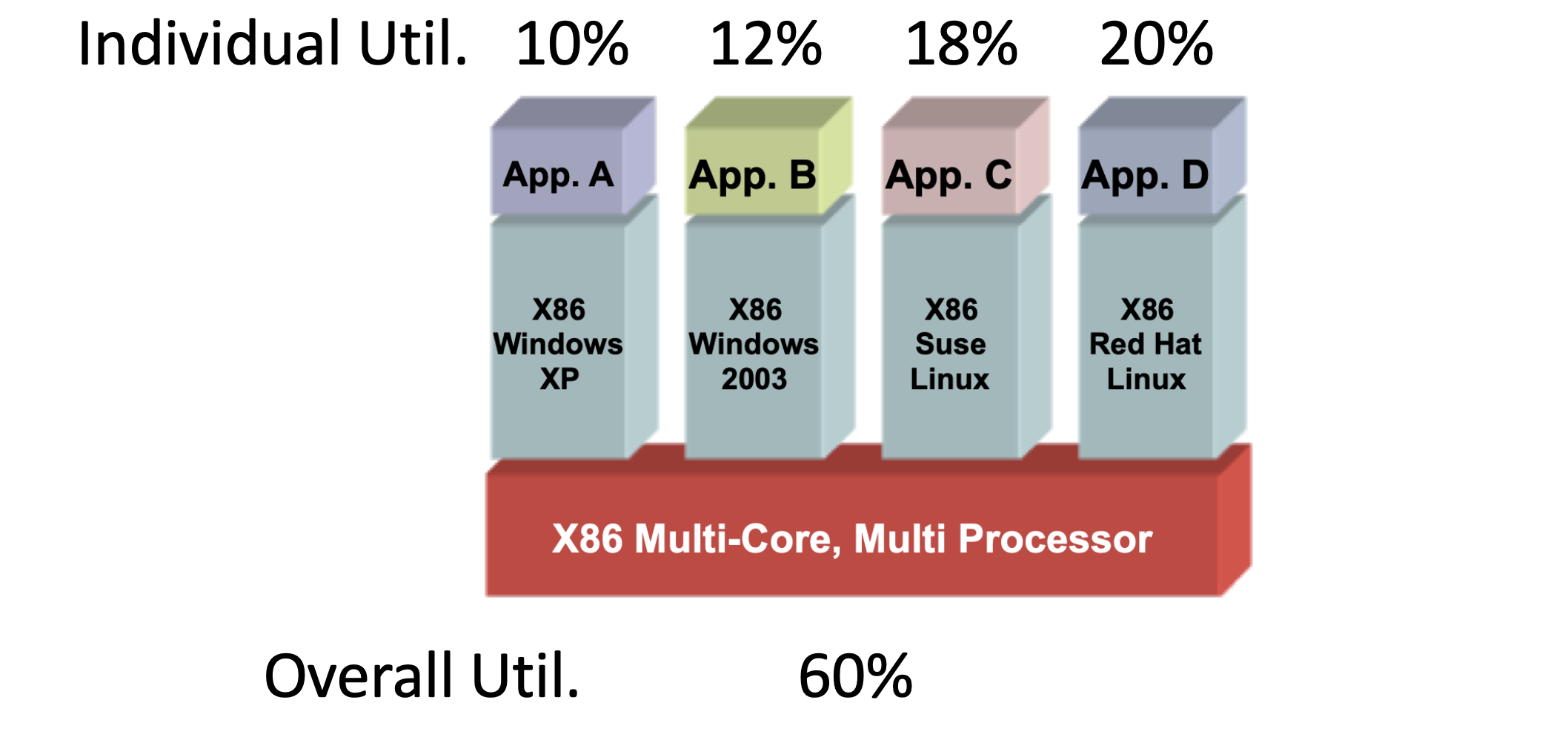

Purpose of Virtualization

The primary purpose of virtualization is to enhance efficiency, flexibility, and scalability. Through virtualization, we can achieve:

- Optimize Resource Usage: Multiple OS instances share resources on a single physical machine, avoiding the waste caused by configuring separate hardware for each application.

- Simplify Management: Administrators can manage and allocate virtual resources through a centralized platform, reducing the need for direct manipulation of physical hardware.

- Enhance Security: Isolation between virtual environments increases system safety and stability, ensuring issues in one VM do not affect others.

- Rapid Deployment & Migration: Quickly create new VMs or migrate existing ones between different physical hosts to meet varying workload demands.

- Disaster Recovery: Since VMs exist as files, backup and recovery processes are more straightforward.

Principles of Virtualization

The Trap and Emulate mechanism is a fundamental approach to implementing virtualization, especially in early full virtualization environments. The core idea is to allow the guest operating system (Guest OS) to run within its own virtual environment while executing most non-privileged instructions directly on the host CPU as if it were running natively. However, when certain sensitive instructions are encountered, instead of being executed directly, they trigger an exception (a trap), which then transfers control to the Virtual Machine Monitor (VMM or Hypervisor).

The ideal is came from Popek & Goldberg (1974)

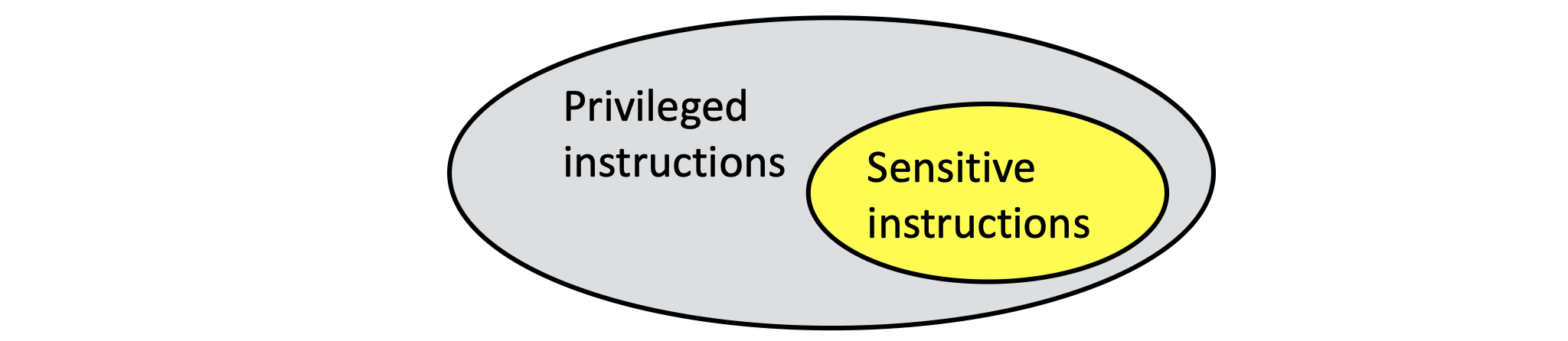

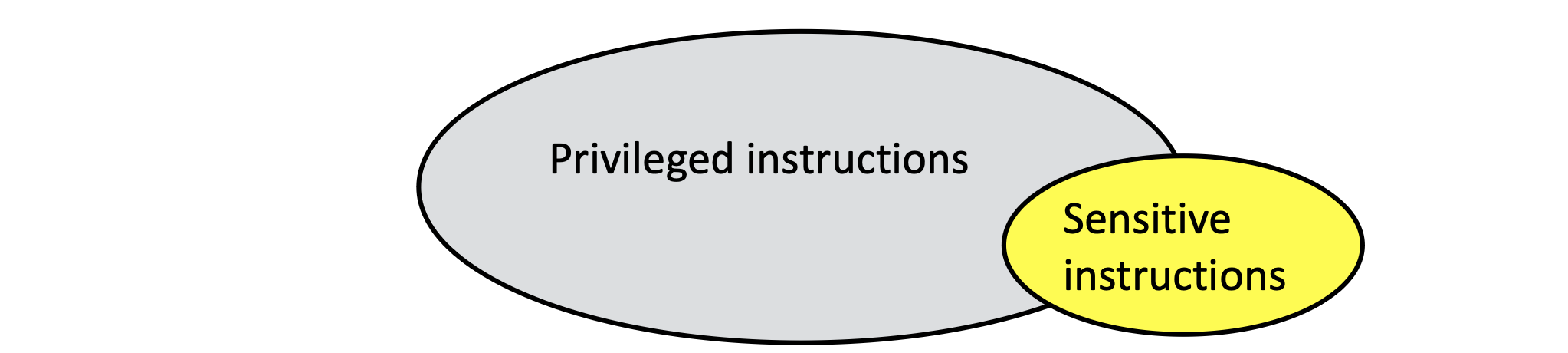

In computer architecture, instructions can be categorized based on their access level to system resources and the scope of their impact. Here are several main classifications of instructions:

- Non-privileged Instructions: These are instructions that can execute in user mode without violating OS security policies. They generally do not alter the global state of the system directly and can run within a VM without VMM intervention.

- Privileged Instructions: Privileged instructions can only run in kernel mode or higher privilege levels. They control and manage hardware resources such as memory management, I/O operations, interrupt handling, and can affect overall system stability. In a virtual environment, they must be managed and emulated appropriately by the VMM.

- Sensitive Instructions: A special set of instructions that can influence the visible state or behavior of the system even though they may not require privileged execution rights. For instance, certain instructions reading clock values might not be privileged but return results specific to the physical hardware, thus requiring interception by the VMM to provide a virtualized response.

The mechanism is based on the prepromise that all sensetive instructions are privileged instructions, and they can trigger a trap. Just like figure blew:

If the prepromise is met, the workflow of Trap and Emulate can be described as follows:

- Normal Execution: Most instructions from the guest OS execute directly on the host CPU since they are non-privileged and do not affect the underlying system state.

- Trap on Sensitive Instructions: When the guest OS attempts to execute a sensitive instruction (e.g., modifying CPU states or accessing protected resources), this triggers a trap, causing control to transfer to the VMM.

- VMM Intervention: Upon receiving the trap, the VMM examines what happened and takes appropriate action to emulate the behavior of that instruction. For example, if the guest OS tries to read the timestamp counter, the VMM might provide a virtualized time value.

- Return to Guest OS: Once the VMM has completed emulating the sensitive instruction, it resumes the execution of the guest OS as if nothing had interrupted it.

This method’s advantage lies in its ability to achieve virtualization without modifying the guest OS, but it also has drawbacks, particularly concerning performance. Each encounter with a sensitive instruction introduces overhead due to the context switch between the guest OS and the VMM.

Moreover, because the x86 architecture was not originally designed for virtualization, some critical instructions could not be easily trapped and emulated, necessitating more complex binary translation techniques to handle them.

Depending on how sensitive instructions are handled and whether hardware support is relied upon, virtualization can be implemented in three main ways:

- Full Virtualization: The VMM fully emulates underlying hardware, enabling unmodified guest OSes to run in a virtual environment. Handling sensitive instructions requires complex binary translation or dynamic compilation, which can lead to performance drops. Early x86 lacked the necessary hardware features for proper handling of sensitive instructions.

- Paravirtualization: Guest OSes are specially designed or modified to be aware of running in a virtual environment and collaborate with the VMM for more efficient resource management. This reduces the need for complex binary translation and offers better performance but requires kernel-level support, not easily adaptable by all OSes.

- Hardware-assisted Virtualization: Modern processors come with dedicated instruction sets supporting virtualization, such as Intel VT-x and AMD-V. This approach combines the benefits of full and paravirtualization, offering near-native performance without modifying guest OSes. Hardware-assisted virtualization allows most non-privileged instructions to execute directly, handling privileged instructions via special mechanisms like VMX root/non-root mode switching.

| Feature | Full Virtualization | Paravirtualization | Hardware-assisted Virtualization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Handling privileged instructions | Binary Translation | Hypercalls | Non-Root / Root Mode |

| Performance | Good | Best | Better |

| Guest OS modifications | No | Yes | No |

| Examples | VMware, VirtualBox | Xen | Xen, VMware, VirtualBox, KVM |

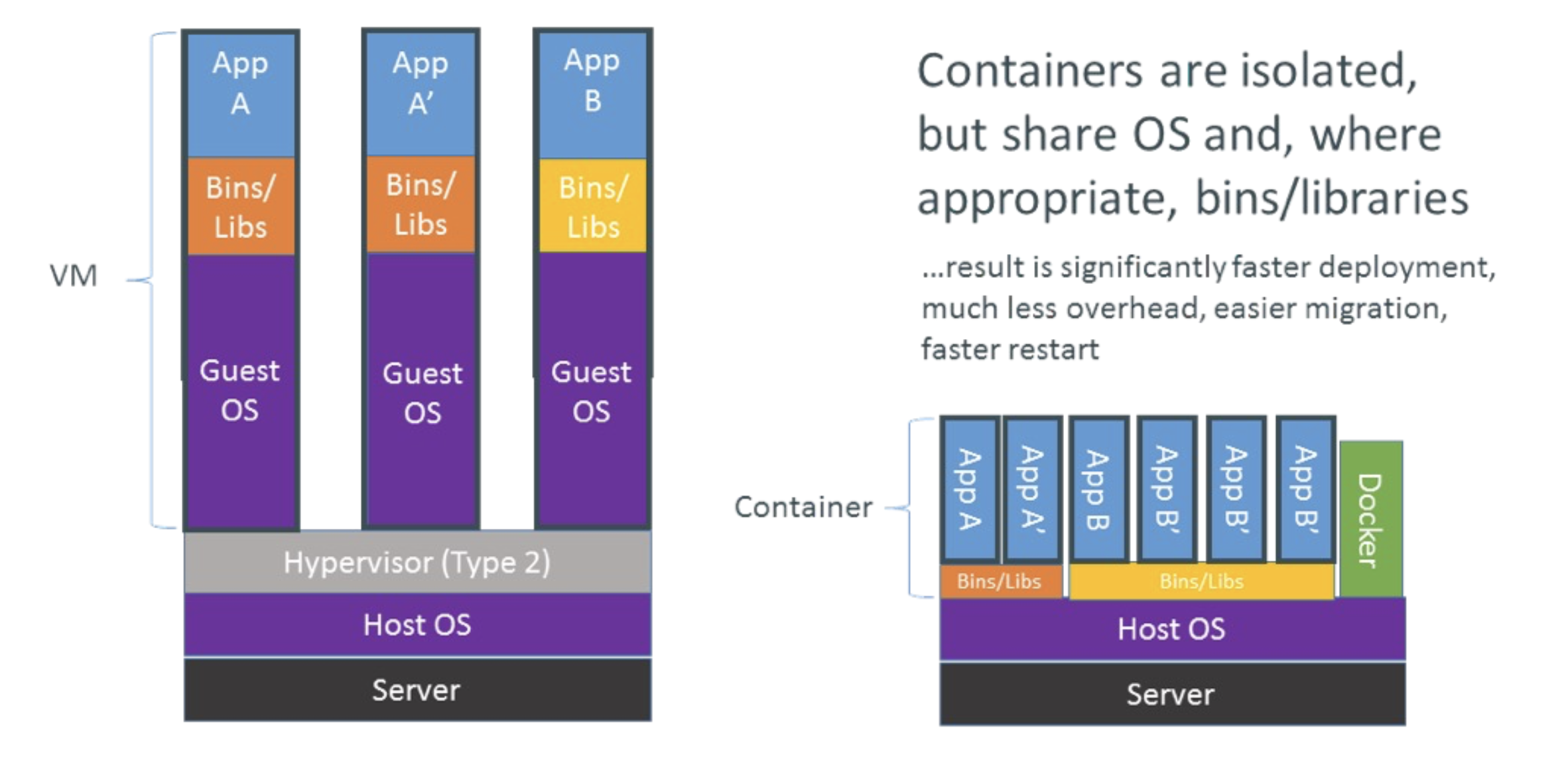

Containerization

Containerization is a lightweight virtualization technology that allows developers to package an application and its dependencies into a standalone unit called a container. Containers share the host machine’s operating system kernel but each has its own file system, CPU, memory, process space, and other resources. This design makes containers more lightweight and efficient compared to traditional VMs, with faster startup times and better portability across different environments. The core components of containerization include:

- Container Engine: Such as Docker Engine, which is software for creating and running containers.

- Image: A read-only template containing the application code and all its dependencies.

- Container: One or more processes instantiated from an image, having isolated working spaces.

The advantage of containerization lies in ensuring that applications run consistently across any environment, from a developer’s laptop to production servers. Additionally, since containers are isolated from each other, if one container encounters issues, it does not affect others.

Also see my blog on Ray - Docker Setup and Ray - Docker Quick Start

Comparison with Virtualization

- Resource Utilization

- Containerization: Containers share the host OS kernel, thus they consume fewer resources and start up quickly, making them suitable for rapid deployment and scaling of microservices architectures.

- Virtualization: Each VM has its own copy of the OS, increasing resource consumption and potentially leading to slower startup times.

- Startup Time

- Containerization: Because there’s no need to boot a full OS, containers can start within seconds.

- Virtualization: VMs require booting an entire OS, which can take several minutes.

- Isolation Level

- Containerization: While containers provide a certain level of application isolation, they share the same kernel, meaning that if there’s a vulnerability in the kernel, all containers could be affected.

- Virtualization: Each VM has its own independent OS kernel, providing stronger security and isolation.

- Management Complexity

- Containerization: Containers are generally easier to manage and deploy, especially when using orchestration tools like Kubernetes for automated management.

- Virtualization: Managing multiple VMs can add complexity, especially concerning network configuration, storage allocation, etc.

- Applicability

- Containerization: Ideal for microservices architecture, CI/CD pipelines, and application environments that require frequent updates and iterations.

- Virtualization: Better suited for scenarios requiring fully isolated environments or running multiple different operating systems, such as hosting various Web applications or legacy systems.

| Containerization | Virtualization | |

|---|---|---|

| Resource Utilization | Fewer resources, quick startup | More resources, slower startup |

| Startup Time | Within seconds | Minutes |

| Isolation Level | Shared kernel, less isolation | Independent kernel, more isolation |

| Management Complexity | Easier to manage | More complex to manage |

| Applicability | Microservices, CI/CD, frequent updates | Legacy systems, multiple OSes, strong isolation |

In summary, both containerization and virtualization have their strengths and weaknesses, and the choice between them depends on specific business needs and technical stacks. For use cases seeking high performance, fast deployment, and good portability, containerization is usually the better option; for situations requiring strong isolation and support for multiple operating systems, virtualization is more appropriate.

Container Orchestration

Container orchestration involves managing and organizing both hosts and Docker containers running on a cluster. As containerized applications become more prevalent, managing a large number of containers and their dependencies becomes increasingly complex. Container orchestration tools simplify this process by automating deployment, scaling, and service discovery, ensuring that applications run efficiently and reliably.

A core challenge in container orchestration is effectively allocating resources, deciding where to schedule containers to meet their CPU, RAM, and disk requirements, and how to track node status for dynamic scaling.

- Scheduling Decisions: The orchestration tool must intelligently select the most suitable node for each container. This involves evaluating available resources on each node (such as CPU cores, remaining memory, storage space) and considering other factors like network latency, topology, and affinity rules.

- Resource Monitoring and Management: To maintain system health, the orchestration tool must continuously monitor the status of all nodes, including resource usage and performance metrics. If a node becomes overloaded or fails, the tool should automatically migrate containers to healthy nodes and dynamically add or remove nodes based on load conditions.

- Scaling Capabilities: When traffic increases, applications may require more instances to handle requests. The orchestration tool should support horizontal scaling, automatically launching new container replicas according to predefined policies, and conversely reducing scale when demand decreases to save resources.

Kubernetes is one of the most popular container orchestration platforms, developed by Google and donated to the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF). It offers a robust feature set for managing complex containerized application environments, including self-healing, rolling updates, service discovery, load balancing, and more.

Distributed Storage Systems

Consider following conditions: (Target Environment)

- Thousands of computers

- Failures are the norm

- Files are huge, but not many

- Write-once, read-many

- I/O bandwidth is more important than latency

Distributed storage systems are architectures that spread data across multiple independent computing nodes, typically composed of inexpensive commodity PCs, each equipped with disk and CPU. Unlike traditional vertical scaling (Scale-Up), distributed storage systems adopt a horizontal scaling (Scale-Out) approach, expanding system performance and capacity by adding more nodes. This method not only provides higher aggregate storage capacity but also offers high I/O bandwidth proportional to the number of machines, enabling parallelized data processing, thereby significantly enhancing overall efficiency. Key features of distributed storage systems include:

- Scalability

- High Storage Capacity

- High I/O Bandwidth

- Parallelized Data Processing

- Fault Tolerance and Reliability

- Cost-effectiveness

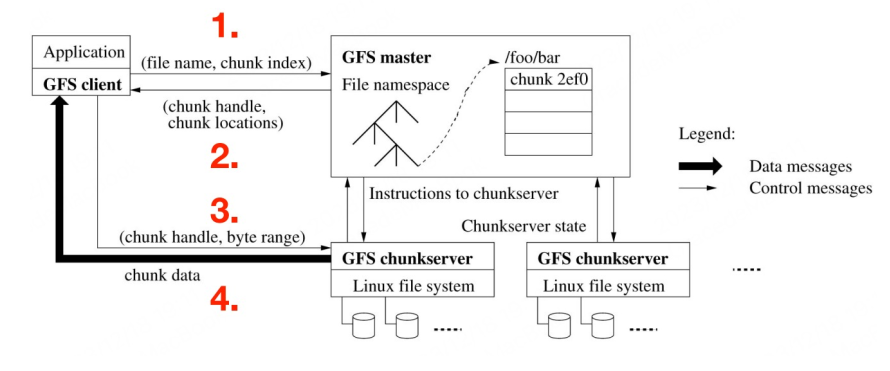

Google File System & Hadoop Distributed File System

GFS and HDFS are two renowned distributed file systems designed to build highly reliable storage systems atop inexpensive and unreliable hardware. Both systems were developed to address the needs of large-scale data storage and processing, particularly in internet companies handling massive volumes of logs, clickstreams, and other big datasets.

Distributed file systems need to run on thousands of computers, failures are common, files are large but not numerous, and are written once and read many times. Additionally, I/O bandwidth is more important than latency.

Hence, the main design of distributed file systems are:

- File stores as/divided into large chunks (blocks)

- Large chunk size: 64/128 MB

- Reduced Metadata Management Overhead: Larger chunks reduce the number of chunks that need to be tracked within the filesystem, lowering metadata management and maintenance costs.

- Improved Transfer Efficiency: For large-scale data transfers, larger chunks can minimize the number of network requests, thereby enhancing overall transfer efficiency.

- Suitability for Large Files: Given that files are typically very large, larger chunks better match this workload characteristic, requiring fewer chunks per file, simplifying management and retrieval processes.

- Reduced Addressing Overhead: Larger chunks mean each chunk contains more data, reducing the time and resources needed to locate and access specific data.

- Reliability through replications

- 1 replication in the same rack, 2+ replications in different racks

- Local Fast Recovery: A replica within the same rack provides rapid data recovery capabilities, especially in the event of localized hardware failures.

- Cross-Rack Redundancy: Multiple replicas in different racks ensure data remains safe and reliable even if an entire rack fails. This layout also disperses risk, increasing system fault tolerance.

- Network Partition Tolerance: Even if network connections between some racks fail, as long as replicas in other racks remain accessible, the system can continue to provide services.

- Single master to coordinate access

- Keep metadata only, file data stored in chunkservers.

- Reduced Master Node Load: The master node only manages metadata without directly handling actual data storage, significantly reducing its workload and improving performance and response times.

- Simplified Recovery Process: If the master node fails, only metadata needs to be recovered, avoiding concerns about massive file data loss or corruption.

- Enhanced Scalability: As the system scales, additional chunkservers can independently store more file data without increasing pressure on the master node.

- Optimized I/O Path: Clients can directly retrieve data from chunkservers rather than going through the master node, optimizing I/O paths and boosting read/write performance.

Limitations

Distributed file systems like GFS (Google File System) and HDFS (Hadoop Distributed File System) are optimized for specific workloads and environments, which also introduces certain limitations:

- Assumes Write-Once, Read-Many Workloads

- Not suitable for frequent writes: These systems assume that data is rarely modified or appended after being written once, making them less efficient for handling datasets that require frequent updates. For instance, they may not perform well with real-time updating log files or frequently changing database records, where other systems designed specifically for such workloads might be more appropriate.

- Metadata management challenges: Frequent write operations necessitate frequent metadata updates by the master node, potentially leading to the metadata server becoming a bottleneck and increasing complexity and maintenance costs.

- Assumes a Modest Number of Large Files

- Small file problem: wasted storage space and metadata server overload. Internal fragmentation and metadata management overhead increase with small files.

- Metadata server load: affects performance

- Emphasizes Throughput Over Latency

- High-latency operations: sacrificed response time

- Not suitable for low-latency requirements: interactive applications, instant messaging services

Distributed Computing Systems

Like Distributed Storage Systems, Distributed Computing Systems also require distributed computing infrastructure to support distributed computing tasks. These systems typically consist of:

- Master Nodes: The central nodes responsible for coordinating the execution of distributed computing tasks, such as scheduling, resource allocation, and monitoring.

- Worker Nodes: These nodes perform the actual computation and provide resources to the master nodes for task execution.

- Client Nodes: These nodes request and receive the results of distributed computing tasks from the master nodes.

MapReduce

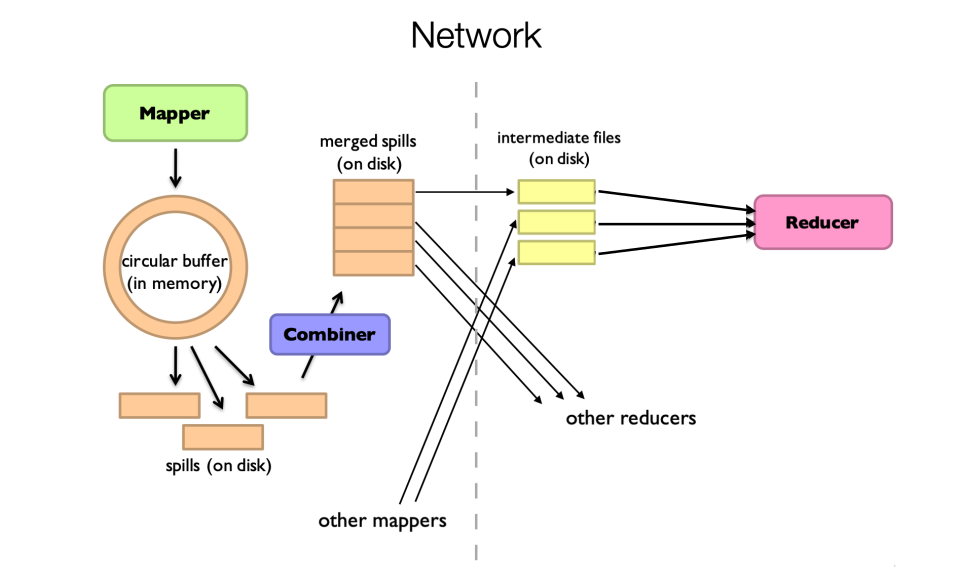

MapReduce is a programming model and its associated implementation for processing and generating large datasets. Programmers only need to specify two functions: map and reduce, while the execution framework handles all other details. Core functions include:

- $map: (k, v) \rightarrow [<k_2, v_2>]$

- Takes an input key-value pair $(k, v)$ and outputs a list of new key-value pairs $[<k_2, v_2>]$.

- The map function is responsible for transforming the input data into intermediate results, often involving splitting, filtering, or preliminary calculations on the input data.

- $reduce: (k_2, [v_2]) \rightarrow [<k_3, v_3>]$

- Receives a key $k_2$ and a list of values $[v_2]$ associated with that key, outputting a list of new key-value pairs $[<k_3, v_3>]$

- The reduce function aggregates the intermediate results, such as summing up values, counting occurrences, or performing other aggregation operations. All values with the same key are processed together.

There are also some function variants, such as:

- $combine: (k, [v]) \rightarrow <k, v>$

- Acts as a local optimization version of reduce. The combine function can perform partial aggregation on the map output locally on each node, reducing the amount of data transferred to the reduce phase.

- It enhances efficiency, especially in scenarios with limited network bandwidth.

- $partition: (k, N_{partitions})$

- Determines how intermediate key-value pairs are assigned to different reduce tasks. Typically, a hash function is used to decide which partition a key should be sent to.

- This function ensures load balancing and controls the distribution of final outputs.

The execution framework handles the following tasks:

- Data Splitting: Divides the input data into multiple chunks for different map tasks to process.

- Task Scheduling: Arranges map and reduce tasks to run on various nodes within the cluster.

- Error Recovery: If a task fails, the framework restarts it to ensure the successful completion of the entire job.

- Status Updates and Monitoring: Provides real-time status information and performance monitoring to help users track job progress.

MapReduce model simplifies large-scale data processing by separating business logic from underlying complexities, allowing developers to focus on writing core algorithms without worrying about the specifics of distributed computing implementations.

In distributed computing environments, particularly within frameworks like MapReduce, the ideal scaling characteristics are:

- Twice the Data, Twice the Running Time: When the input data size doubles, the job completion time should also double.

- Twice the Resources, Half the Running Time: When the available computational resources (such as the number of nodes) double, the job completion time should halve.

However, achieving these ideal scaling characteristics in practice is often challenging due to Challenges of Synchronization and Communication:

- Synchronization Requires Communication: In distributed systems, multiple tasks need to coordinate and synchronize to ensure correctness and consistency. This synchronization typically involves inter-node communication, such as sending heartbeat messages, status updates, or intermediate results.

- Communication Impacts Performance: Network communication between nodes is often a bottleneck. Compared to local processing speeds, network latency and bandwidth limitations significantly degrade overall performance. Excessive communication not only increases latency but can also lead to network congestion, further slowing down system execution.

Therefore, to mitigate the negative effects of communication, optimization strategies should focus on Avoid Communication, Perform Local Aggregation as Much as Possible:

Perform preliminary aggregation or compression of data during the map phase to reduce network load. Run a local reduce function on each node to aggregate data with the same key before sending it over the network. This what we call Combiner.

From MapReduce to Spark

To better understand the transition from MapReduce to Spark, we will delve into the differences between the two, the improvements introduced by Spark, and the specific workflows. Here’s a detailed analysis:

- Limitations of MapReduce:

- Disk I/O Bottleneck: In MapReduce, intermediate results are written to disk after each task. Even simple iterative algorithms result in numerous disk read/write operations, leading to performance degradation.

- Less Flexible Execution Model: The task scheduling in MapReduce is batch-oriented, meaning all map tasks must complete before any reduce tasks can begin. This strict sequential execution limits job flexibility and efficiency.

- High Cost of Fault Recovery: If a node fails during a MapReduce job, it may require rolling back the entire job or relying on checkpoint files to recover lost data. This increases the cost and complexity of fault recovery.

- Improvements Introduced by Spark:

- In-Memory Data Sharing: Spark allows intermediate results to remain in memory, reducing unnecessary disk I/O. This is particularly important for iterative algorithms (such as machine learning training) and interactive queries, where repeated access to the same dataset is required without reloading from disk each time.

- More Flexible Execution Model: Spark introduces Resilient Distributed Datasets (RDDs), which support various transformation operations (map, filter, join, etc.). These operations can be combined at different stages, forming a more flexible task scheduling approach. Additionally, Spark supports complex computational graphs, allowing tasks to dynamically adjust based on actual needs.

- Efficient Fault Recovery Mechanism: Spark achieves efficient fault recovery by maintaining lineage information for RDDs. When certain partitions are lost, the system can recompute these partitions based on their lineage, without needing to redo the entire job or rely on checkpoint files. This not only reduces the cost of fault recovery but also simplifies system implementation.

| Feature | MapReduce | Spark |

|---|---|---|

| Data Storage | Intermediate results written to disk | Intermediate results kept in memory |

| Execution Model | Strictly staged (Map -> Shuffle -> Reduce) | Elastic task scheduling, supporting complex computational graphs |

| Fault Recovery | May require rollback or reliance on checkpoint files | Efficient recovery based on lineage information |

| API | Lower-level, primarily supporting Java | Provides higher-level abstractions, supporting multiple programming languages |

An RDD (Resilient Distributed Dataset) is a fundamental abstraction in Apache Spark that represents an immutable, partitioned collection of data items. RDDs provide efficient operations on large datasets and fault tolerance, serving as the backbone for Spark’s big data processing capabilities. Here’s a summary of key aspects of RDDs:

- Set of Partitions: An RDD consists of a set of logical partitions, each representing a portion of the dataset. These partitions can be distributed across different nodes in a cluster and processed in parallel.

- List of Dependencies on Parent RDDs: Each RDD maintains a list of dependencies on its parent RDD(s). This lineage information tracks how the RDD was derived from other RDDs. In case a partition is lost, it can be recomputed based on this lineage without needing to roll back the entire job.

- Function to compute a partition given its parents: For each partition, an RDD defines a function that specifies how to compute the contents of that partition given its parent RDD(s). This function is executed dynamically when needed, meaning computation only occurs when the data is actually accessed, known as lazy evaluation.

- Partitioner (Hash, Range): RDDs may optionally specify a partitioner to determine which partition an item should belong to. Common partitioning strategies include hash partitioning and range partitioning. If no partitioner is specified, hash partitioning is used by default.

- Preferred Locations for Each Partition: RDDs can also specify preferred locations for each partition, indicating which nodes are best suited to store and process the data. Typically, these locations are chosen based on where the data physically resides, reducing network overhead and improving efficiency.

Still, let’s look at a real-world example of using MapReduce in Spark. Here’s a Python script that uses Spark to perform word count on a text file:

from pyspark import SparkConf, SparkContext

conf = SparkConf().setAppName('Word Counts')

sc = SparkContext(conf=conf)

# Load the text file

lines = sc.textFile('hdfs:///user/hadoop/wordcount/input.txt')

# Split the lines into words and count the occurrences of each word

word_counts = lines.flatMap(lambda x: x.split(' ')) \

.map(lambda x: (x, 1)) \

.reduceByKey(lambda x, y: x + y)

# Save the word counts to a text file

word_counts.saveAsTextFile('hdfs:///user/hadoop/wordcount/output')

RDD (Resilient Distributed Dataset) is the basic abstraction of Spark and represents an immutable, partitioned data collection. DataFrame is an RDD with schema information, which provides a higher-level API and a more efficient execution method. DataFrame not only maintains the immutability and lineage information tracking of RDD, but also introduces rich built-in functions, optimized query execution, and support for multiple data sources, making data analysis simpler and more efficient. Here is a comparison between RDD and DataFrame:

from pyspark.sql import SparkSession

from pyspark.sql.functions import explode, split, col

spark = SparkSession.builder.appName('Word Counts').getOrCreate()

lines_df = spark.read.text('hdfs:///user/hadoop/wordcount/input.txt')

words_df = lines_df.withColumn('word', explode(split(col('value'), ' '))).select('word')

word_counts_df = words_df.groupBy('word').count()

word_counts_df.write.csv('hdfs:///user/hadoop/wordcount/output', header=True)

spark.stop()

Comments