Diffie-Hellman and RSA

Diffie-Hellman and RSA are two popular algorithms for secure communication. They fixed the problem of former cryptography, which was the key distribution problem and digital signature problem based on number theory.

Table of Contents

- Problems of former cryptography

- Introduction of Diffie-Hellman and RSA

- Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange Protocol

- RSA Algorithm

- Elliptic Curve Cryptography

Problems of former cryptography

Key Distribution Problem

In traditional symmetric encryption systems, both communicating parties need to share a secret key. This key must be securely distributed to all message senders and receivers before communication begins. However, this key distribution process has the following issues:

- Security Issues: If the key is intercepted during transmission, the security of the entire communication will be severely compromised.

- Management Complexity: As the number of users increases, the number of keys that need to be managed grows exponentially. For example, if there are $ n $ users, each pair of users requires an independent key, resulting in a total of $ \frac{n(n-1)}{2} $ keys that need to be managed.

- Initial Trust Issue: How to securely distribute keys in the absence of pre-established trust is a significant challenge.

Public-key cryptography addresses these issues by introducing a pair of keys—public and private keys:

- Public Key: Can be publicly distributed and used for encrypting data or verifying signatures.

- Private Key: Must be kept confidential and used for decrypting data or generating signatures.

Through this method, communication parties can securely exchange information over an insecure channel without needing to share any secret information in advance. For example, Alice can use Bob’s public key to encrypt a message, and then Bob can use his own private key to decrypt the message. Thus, even if the message is intercepted during transmission, the attacker cannot decrypt it without the private key.

Digital Signature Problem

In the era of paper documents, signatures were a common way to verify the authenticity of documents. However, the advent of electronic documents has brought new challenges:

- Non-repudiation: How to ensure that electronic signatures cannot be denied?

- Integrity: How to ensure that electronic documents have not been tampered with during transmission?

- Authentication: How to ensure that the electronic signature was indeed generated by a specific person?

Public-key cryptography solves these problems through digital signature technology:

- Signature Generation: The sender uses their own private key to sign the hash value of the message, generating a digital signature.

- Signature Verification: The receiver uses the sender’s public key to verify the digital signature. If the signature verification is successful, the receiver can be confident that:

- The message was indeed generated by the claimed sender.

- The message has not been altered during transmission.

- The sender cannot deny sending the message.

Introduction of Diffie-Hellman and RSA

The Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol (often abbreviated as Diffie-Hellman or DH) is a security protocol that allows two parties to establish a shared secret over an insecure communication channel. This shared secret can be used to encrypt subsequent communications. The protocol was proposed by Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman in 1976 and is the first widely used key exchange algorithm.

At the same year, Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman introduced the concept of public-key cryptography, demonstrating the possibility of public-key cryptography. They proposed a framework where two communicating parties can negotiate a shared key over an insecure channel without having to exchange any secret information in advance.

However, at the time, Diffie and Hellman did not immediately propose a specific, practical implementation of public-key cryptography. Instead, they issued a challenge to their colleagues, hoping that someone could come up with a feasible solution. This challenge was answered in 1977 by three researchers from MIT: Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Leonard Adleman. They invented a public-key encryption algorithm based on number theory, known as the RSA algorithm. The name RSA comes from the initials of the three inventors.

| Feature | Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange Protocol | RSA Algorithm |

|---|---|---|

| Main Function | Negotiate shared key | Data encryption and digital signatures |

| Application Scenario | Session key negotiation | Data encryption, signature verification |

| Dynamism | Generates new key for each communication | Keys can be used long-term |

| Security | Vulnerable to man-in-the-middle attacks | Based on the difficulty of factoring large integers |

| Forward Secrecy | Provides forward secrecy | Does not provide forward secrecy |

| Computational Overhead | Low | High |

| Applicable Scenarios | Key negotiation over insecure networks | Scenarios requiring long-term security |

Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange Protocol

Prerequisites Mathematics

To understand the Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol, it is important to have a solid understanding of basic number theory and group theory. We will start by defining some basic terms:

A group $ G $ is a set of elements $ G = { g_1, g_2, \ldots, g_n } $ assoiated with a binary operation $ \circ $ called the group operation and meet the following requirements:

- Close

- Associative

- Identity

- Inverses

The order of a group $ G $ is the number of elements in the group. If the order of a group $ G $ is finite, it is called a finite group, otherwise it is called an infinite group. We denote the order of a group $ G $ with the symbol $\text{order}(G)$ or $|G|$.

If a group $ G $ also satisfies commutative, then it is called a commutative group or a abelian group.

- Commutative

If a group $ G $ also satisfies following properties, then it is called a cyclic group. We call $ g’ $ the generator of the group.

- Cyclic

If $|G|$ is finite, then it is called a finite cyclic group, otherwise it is called an infinite cyclic group.

A cyclic group $ G $ is necessarily abelian, because the power operation is commutative. Start with a generator $ g’ $:

\[\forall g_i, g_j \in G, \exists n_i, n_j \in \mathbb{N} \rightarrow g_i = g'^{n_i}, g_j = g'^{n_j}\]By the close property, we have:

\[g_i \circ g_j \in G \rightarrow g'^{n_i + n_j} \in G \rightarrow g'^{n_j} \circ g'^{n_i} \in G \rightarrow g_j \circ g_i \in G\]Here we have defined all things we need to understand the Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol. Now, let’s focus on Multiplicative Group Modulo $ p $. Consider the multiplicative group modulo $ p $, denoted $ \mathbb{Z}_p^* $ where $ p $ is a prime. This group contains all integers from 1 to $ p-1 $ that are coprime with $ p $. The order of $ \mathbb{Z}_p^* $ is $ p-1 $. If $ g $ is a generator of $ \mathbb{Z}_p^* $, then the powers of $ g $ generate all elements of $ \mathbb{Z}_p^* $ That is, for any $ a \in \mathbb{Z}_p^* $, there exists an integer $ k $ such that $ a = g^k \mod p $.

The Discrete Logarithm Problem (DLP) is an important problem in number theory and forms the basis of the security of many public-key cryptography algorithms, such as the Diffie-Hellman key exchange and the ElGamal encryption algorithm. Simply put, the difficulty of computing discrete logarithms refers to the high computational complexity of solving the discrete logarithm problem, making it practically infeasible to solve within a reasonable time frame in real-world applications.

Suppose we have a finite cyclic group $ G $ and a generator $ g $. For any group element $ y \in G $, the discrete logarithm problem can be stated as follows: given $ y $ and $ g $, find an integer $ x $ such that:

\[y = g^x \mod p\]where $ p $ is a large prime number, and $ g $ is a primitive root modulo $ p $. This problem is NP-hard.

Procedures

- First, Alice and Bob agree on a large prime $p$, and $g$, such that $g$ is a generator mod $n$. The numbers don’t have to be secret.

- Alice chooses a random large integer x and sends Bob $X$, where \(X = g^x \mod p\)

- Bob chooses a random large integer $y$ and sends Alice $Y$, where \(Y = g^y \mod p\)

- Alice computes \(K = Y^x \mod p\)

- Bob computes \(K = X^y \mod p\)

The shared secret $K$ is a number that is only known to both Alice and Bob. We can show that the shared secret is the same as the discrete logarithm of $K$ with respect to $g$ modulo $n$: \(K = Y^x \mod p = g^{yx} \mod p = g^{xy} \mod p = X^y \mod p = K\)

An attacker can obtain the values of $X$, $Y$, $g$, and $p$. However, to derive the secret key $K$, they must solve the discrete logarithm problem: given $X$, $g$, and $p$, determine $x$ such that $X = g^x \mod p$. This task is computationally challenging, ensuring the security of the key.

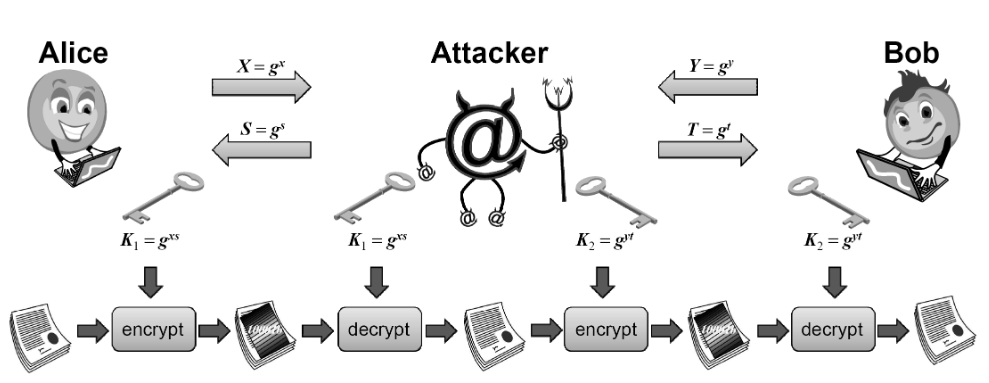

Challenge from MITM Attack

One major issue with the Diffie-Hellman protocol is the lack of authentication, which makes it vulnerable to man-in-the-middle attacks. The basic idea of a man-in-the-middle attack is that the attacker (Eve) intercepts and modifies the messages between the two communicating parties (Alice and Bob), thereby establishing separate shared keys with each party without their knowledge.

There are a number of techniques to defend against such an attack:

- Each person can have a “somewhat permanent” public and secret number, instead of creating one for each message exchange. This can be considered to be a kind of Digital Phonebook.

- If Alice and Bob share some kind of secret which then can use to authenticate each other, then they can use this secret to verify each other’s messages indeed came from the person they expected.

Encryption with Diffie-Hellman

One disadvantage of the Diffie-Hellman protocol is that for communication to occur, Alice and Bob need to perform an active key exchange, which means they must both be online simultaneously. This can be inconvenient in certain situations.

To overcome this limitation, the following method can be used to enable Alice and Bob to communicate securely at any time without needing to be online simultaneously.

- Alice computes a personal public key, consisting of $(p_A, g_A, T_A)$ where $T_A = g_A^{S_A} \mod p_A$, and publishes on a reliable public place. $S_A$ is a secret number known only to Alice.

- Bob does the same, publishing $(p_B, g_B, T_B)$.

- If Alice wants to send Bob an encrypted message, she picks a random number $S_A’$ and computes $K_{AB} = T_B^{S_A’} \mod p_B$. Also, she computes $T_A’ = g_B^{S_A’} \mod p_B$. $T_{AB}$ is the shared secret between Alice and Bob.

- She uses $K_{AB}$ to encrypt the message using any secret key cipher (such as AES). She then needs to send $T_A’$.

- Bob then uses $T_A’$ to compute $K_{BA} = T_A’^{S_B} \mod p_B$. He then uses $K_{BA}$ to decrypt the message using the secret key cipher.

We can show that $T_{AB}$ and $T_{BA}$ are the same as following:

\[T_{AB} = T_B^{S_A'} \mod p_B = (g_B^{S_B})^{S_A'} \mod p_B = (g_B^{S_A'})^{S_B} \mod p_B = T_A'^{S_B} \mod p_B = T_{BA}\]Diffie-Hellman and Safe Primes

- Basic Concepts:

- Diffie-Hellman Protocol: Works with any prime $ p $ and any generator $ g $, but without additional mathematical properties, the security is lower.

- Safe Prime: A prime $ p $ is a safe prime if $ (p - 1)/2 $ is also a prime.

- Why Use Safe Primes:

- Enhanced Security: Using safe primes increases the difficulty for attackers to solve the discrete logarithm problem, especially in resisting small subgroup attacks.

- Mathematical Properties: Safe primes ensure that $ p - 1 $ has a large prime factor, which helps improve the security of the protocol.

- Specific Requirements:

- Choosing a Safe Prime: Ensure $ p $ is a prime and $ (p - 1)/2 $ is also a prime.

- Choosing a Generator: Select a generator $ g $, typically a power of 2, such as $ g = 2 $ or $ g = 3 $, to ensure the generated subgroup has good mathematical properties.

RSA Algorithm

The RSA algorithm is an asymmetric (or public-key) encryption algorithm proposed in 1977 by Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Leonard Adleman, for whom the algorithm is named. It plays a crucial role in secure data transmission and is widely used across various applications such as secure web browsing, email encryption, digital signatures, and more.

The security of the RSA algorithm is based on the difficulty of factoring large integers. While multiplying two large prime numbers together is relatively easy, determining the original prime factors from the product is computationally intensive and time-consuming, especially when the primes are sufficiently large.

Prerequisites Mathematics

Number Theory is the key to understanding the RSA algorithm. It provides a framework for analyzing and manipulating large integers. To understand the RSA algorithm, we need to discover following theorems:

Euler’s totient function, denoted as $\varphi(n)$, represents the number of positive integers less than or equal to $n$ that are coprime with $n$. Formally, for any positive integer $n$,

\[\varphi(n) = |\{k \in \mathbb{Z} : 1 \leq k \leq n, \gcd(k, n) = 1\}|\]To calculate the value of $\varphi(n)$, we need to perform a number of operations on the prime factors of $n$.

- Prime $p$: If $n$ is a prime number $p$, then $\varphi(p) = p - 1$.

- Prime Power $p^k$: If $n$ is a power of a prime $p$, i.e., $p^k$, then $\varphi(p^k) = p^k (1 - \frac{1}{p})$.

- Two Coprime Numbers $m$ and $n$: If $m$ and $n$ are coprime, then $\varphi(mn) = \varphi(m)\varphi(n)$.

- Any Positive Integer $n$: Let the standard factorization of $n$ be $n = p_1^{k_1} p_2^{k_2} … p_m^{k_m}$, where $p_i$ are distinct primes, then

Euler’s Theorem is a statement that:

\[\forall a, n \in \mathbb{Z}^*, \gcd(a, n) = 1 \rightarrow a^{\varphi(n)} \equiv 1 \mod n\]Proof is a little bit complicated. Consider the set $G = {g_1, g_2, …, g_{\varphi(n)}}$ of all positive integers less than $n$ and coprime with $n$. For any integer $a$ coprime with $n$, multiplying each element in $G$ by $a$ and taking modulo $n$ yields a new set $H = {ag_1 \mod n, ag_2 \mod n, …, ag_{\varphi(n)} \mod n}$. The fact $ G = H $ can be shown by Uniqueness and Completeness.

- Uniqueness: Assume there exist two distinct elements $g_i, g_j \in G$ such that $ag_i \equiv ag_j \pmod{n}$. Since $a$ and $n$ are coprime, we can multiply both sides by the modular inverse of $a$ (which exists by definition), leading to $g_i \equiv g_j \pmod{n}$, which contradicts the assumption that $g_i$ and $g_j$ are distinct. Therefore, all elements in $H$ are unique.

- Completeness: Each element $g_i$ in $G$ is coprime with $n$, and since $a$ is also coprime with $n$, $ag_i$ remains coprime with $n$. Thus, $ag_i \mod n$ is still a positive integer less than $n$ and coprime with $n$, meaning it belongs to the original set $G$. This implies $H$ contains all elements of $G$, just in a different order.

Therefore, $H$ is simply a permutation of $G$. Consequently, the product of all elements in $H$ is congruent to the product of all elements in $G$ modulo $n$:

\[\prod_{i=1}^{\varphi(n)} g_i \equiv \prod_{i=1}^{\varphi(n)} ag_i \pmod{n}\] \[\prod_{i=1}^{\varphi(n)} g_i \equiv a^{\varphi(n)} \cdot \prod_{i=1}^{\varphi(n)} g_i \pmod{n}\]Dividing both sides by $\prod_{i=1}^{\varphi(n)} g_i$ (this is valid because each $g_i$ is coprime with $n$), we get:

\[a^{\varphi(n)} \equiv 1 \pmod{n}\]This completes the proof of Euler’s theorem.

Multiplicative Inverse: Given two coprime positive integers $a$ and $m$, if there exists an integer $b$ such that $ab \equiv 1 \pmod{m}$, then $b$ is called the multiplicative inverse of $a$ modulo $m$. There are ways to compute the multiplicative inverse:

-

Fermat’s Little Theorem: When $m$ is a prime, for any integer $a$ coprime with $m$, $a^{m-1} \equiv 1 \pmod{m}$. Therefore, $a^{m-2}$ serves as the multiplicative inverse of $a$ modulo $m$.

-

Extended Euclidean Algorithm: For general $m$ (not necessarily prime), the extended Euclidean algorithm can find the multiplicative inverse. This algorithm not only computes the greatest common divisor $\gcd(a, m)$ but also finds integers $x$ and $y$ such that $ax + my = \gcd(a, m)$. If $a$ and $m$ are coprime, i.e., $\gcd(a, m) = 1$, then $x$ is the multiplicative inverse of $a$ modulo $m$.

The security of RSA primarily relies on several aspects:

-

Integer Factorization Problem: Given a large composite number $n=pq$, where $p$ and $q$ are large primes, finding $p$ and $q$ is computationally difficult. This assumption is central to RSA’s security. There is no known efficient algorithm to factorize $n$ within a reasonable time frame, especially when $p$ and $q$ are sufficiently large.

-

Discrete Logarithm Problem: Although RSA does not directly rely on the discrete logarithm problem, solving for $d$ given $e$ and $\varphi(n)$ is akin to solving a similar problem. This difficulty stems from $\varphi(n)$ being unknown while $n$ is public, making it hard for an attacker to find $d$.

Procedures

- Key Generation:

- Choose two distinct large prime numbers, $p$ and $q$.

- Compute $n = p \times q$; $n$ is the modulus used in both the public and private keys and its bit-length determines the key size.

- Compute Euler’s totient function, $\varphi(n) = (p-1)(q-1)$.

- Select an integer $e$, which is less than $\varphi(n)$ and coprime to $\varphi(n)$, to serve as part of the public key.

- Compute $d$ as the modular multiplicative inverse of $e$ modulo $\varphi(n)$, which is the private key.

- Key Allocation:

- The public key consists of ${e, n}$ and can be shared openly.

- The private key consists of ${d, n}$ and should be kept secret.

- Encryption: Assuming $M$ is the plaintext message (where $M < n$), it is encrypted using the recipient’s public key to produce ciphertext $C = M^e \mod n$.

- Decryption: The receiver decrypts the ciphertext using their own private key, computing the original plaintext $M = C^d \mod n$.

For public-key system, we can use the public key to encrypt a message and the private key to decrypt it to achieve secure communication, on the other hand, we can use the private key to encrypt a message and the public key to decrypt it to achieve identity authentication. Hence RSA can also be used for digital signatures.

We can proof that $M$ remains unchanged in the encryption and decryption process, i.e., $M = C^d \mod n = M^{ed} \mod n$. Because $d$ is the multiplicative inverse of $e$ modulo $\varphi(n)$, we can rewrite it as:

\[ed \equiv 1 \pmod{\varphi(n)} \rightarrow ed = \varphi(n)k + 1\] \[M^{ed} \mod n = M^{\varphi(n)k + 1} \mod n = (M^{\varphi(n)})^k M \mod n\]By Euler’s theorem, we have:

\[M^{\varphi(n)} \equiv 1 \pmod{n}, \text{ where } \gcd(M, n) = 1\]Hence, $M$ remains unchanged in the encryption and decryption process:

\[M^{ed} \mod n = M^{\varphi(n)k + 1} \mod n = M \mod n\]Practical Considerations

In practice, the prime numbers $p$ and $q$ are typically hundreds or thousands of bits long, ensuring that $n$ is sufficiently large to maintain security against factorization attacks. Moreover, because RSA is computationally expensive for encrypting large amounts of data directly, it is often combined with symmetric encryption algorithms: RSA encrypts a symmetric key, which is then used to encrypt the actual data being transmitted.

Additionally, RSA operations are not only used for confidentiality but also for authentication, integrity, and non-repudiation through digital signatures. In real-world implementations, padding schemes like OAEP (Optimal Asymmetric Encryption Padding) for encryption and PSS (Probabilistic Signature Scheme) for signing are used to enhance security and prevent certain types of attacks.

Elliptic Curve Cryptography

This section provides an overview of Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC), a cryptographic algorithm that uses elliptic curve points for key exchange and public-key encryption. We will not focus on the mathematical details, but instead provide a high-level overview of the algorithm and its applications.

Known Subexponential Algorithms

- RSA and Diffie-Hellman:

- There are known subexponential (but superpolynomial) algorithms for breaking RSA and Diffie-Hellman.

- For RSA, the most effective known attack is the General Number Field Sieve (GNFS).

- For Diffie-Hellman, the Index Calculus Method is a known subexponential algorithm.

Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC)

- Advantages of ECC:

- No known subexponential algorithms for breaking ECC.

- ECC is more secure for a given key size compared to other forms of cryptography.

- Example: A 256-bit ECC key provides security equivalent to a 3072-bit RSA key.

- ECC Diffie-Hellman (ECDH):

- Key exchange protocol using elliptic curve points.

- Example: Alice and Bob use elliptic curve point multiplication to negotiate a shared secret key.

- ECC ElGamal (EC-ElGamal):

- Public key encryption algorithm using elliptic curve points.

- Example: Alice uses Bob’s public key to encrypt a message, and Bob uses his private key to decrypt it.

- Other ECC-Based Schemes:

- Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA): Efficient and secure digital signatures.

- Elliptic Curve Key Encapsulation Mechanism (ECKEM): Securely encapsulates and decapsulates symmetric keys.

Summary

| Feature | RSA and Diffie-Hellman | Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) |

|---|---|---|

| Known Attacks | Subexponential (GNFS, Index Calculus) | None known (subexponential) |

| Security for Key Size | Less secure for smaller key sizes | More secure for smaller key sizes |

| Efficiency | Higher computational overhead | Lower computational overhead |

| Applications | Widely used in SSL/TLS, digital signatures | Widely used in SSL/TLS, digital signatures, key exchange |

Comments