Web Security Overview

Web security is a broad topic that covers a wide range of topics related to the security of web applications. It involves the protection of websites, web applications, and web services from unauthorized access, use, disclosure, disruption, modification, or destruction. It also involves the protection of user data and ensuring the integrity of the system by preventing unauthorized access and malicious activities.

Web security is important because web applications are often the primary interface between an organization and its customers, partners, or employees. Web applications are also the primary target of attackers, as they can provide access to sensitive information and systems. Therefore, it is essential to ensure that web applications are secure and can withstand various types of attacks.

Table of Contents

- Web Basics

- Attack Scenarios and Countermeasures

Web Basics

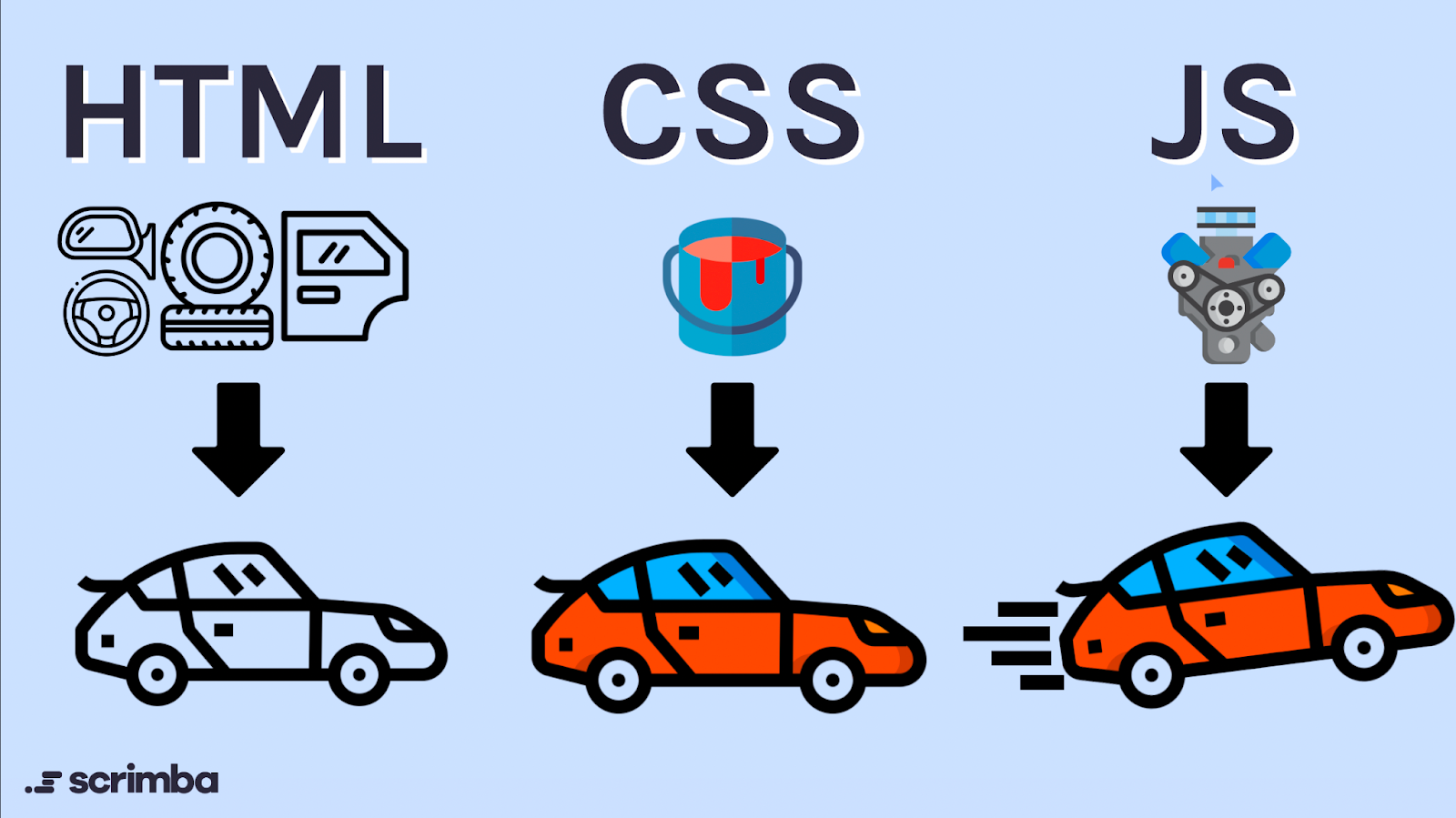

Before we dive into web security, let’s understand the basics of web development. Basically, a web page is a collection of HTML, CSS, and JavaScript that creates a dynamic and interactive experience for users. And beyond that, transporting data between the server and the client using HTTP, HTTPS, and TLS/SSL. In addition, cookies, JWT, and session management are also important mechanisms for identifying and managing state in web applications.

HTML, CSS, and JavaScript

Web development is a diverse field that encompasses many different technologies. HTML, CSS, and JavaScript are three of the most commonly used technologies used in web development.

Together, HTML, CSS, and JavaScript form the core technologies essential for web development. They each serve distinct purposes and when combined, enable the creation of engaging, functional, and visually appealing web applications. Each technology has its own unique features and capabilities that allow developers to create dynamic and interactive web pages.

HTML (HyperText Markup Language)

HyperText Markup Language is the standard markup language for creating the structure and content of web pages. It uses tags to define elements such as headings, paragraphs, links, and multimedia components like images and videos. HTML can also embed scripts and additional media through plugins, enhancing the page with dynamic content and interactive features. To summarize its functions:

- Define the semantic structure of web page content.

- Contains multimedia elements such as pictures, videos.

- Use forms to collect user input.

- Additional media types (e.g., PDF files, Flash animations) can be embedded via plug-ins.

CSS (Cascading Style Sheets)

Cascading Style Sheets is used to style and layout web pages by controlling the visual presentation of HTML or XML documents. It separates content from design, making it easier to maintain and update the appearance of websites. CSS supports responsive design, ensuring that web pages look good on all devices and screen sizes. Developers often use preprocessors like SASS or LESS to write more efficient and modular CSS code. To summarize its functions:

- Control the layout, colors, fonts, and other visual attributes of your web pages.

- Content can be separated from performance for easy maintenance and design updates.

- Support responsive design to adapt pages to different screen sizes.

- Allows Developers to write more concise, modular code using preprocessors (E.G., SASS, LESS).

JS (JavaScript)

JavaScript is a versatile, multi-paradigm programming language primarily used for web development. Initially designed to run in client-side browsers, it has since evolved to server-side applications (e.g., Node.js). JavaScript allows for dynamic content updates and interaction with the user without reloading the entire page. It can handle events, manipulate the Document Object Model (DOM), and communicate asynchronously with servers via AJAX. Summarizing its functions:

- Dynamically modify web page content and styles.

- Handle and react to user events (e.g., clicks, scrolls).

- Send an asynchronous request to the server (AJAX) to update part of a web page without reloading the entire page.

- Manipulate the DOM (Document Object Model), which is a structured representation of an HTML document.

- Implement complex interactions and features, such as games, real-time communication, and more.

- Build server-side applications with Node.js.

However, due to its ability to interact with the user’s environment, it poses potential security risks if not properly managed, such as Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) attacks and clickjacking.

HTTP, HTTPS, and TLS/SSL

In the realm of web communication, data transfer is essential. Various protocols facilitate the exchange of information between clients and servers, ensuring seamless connectivity and interaction across the internet. From HTTP to HTTPS, these protocols play a crucial role in ensuring secure and reliable data transfer. Here’s an overview of the protocols involved in web communication:

HTTP (HyperText Transfer Protocol)

HyperText Transfer Protocol is an application-layer protocol used for data exchange between clients and servers on the internet. It operates primarily over TCP and typically uses port 80 by default.

- Characteristics

- Stateless: HTTP is stateless, meaning each request is independent, and the server does not retain any information about previous requests. Each new request must carry all necessary information because the server does not remember prior interactions.

- Simple and Fast: Designed to be simple and easy to implement, allowing quick connections and scalability. Flexible: Supports the transmission of any type of data object, provided both parties know how to handle the data. Request-Response Model: All communications are initiated by the client making a request, followed by the server responding with data or actions.

- Plaintext Transmission: Early versions of HTTP transmitted data in plaintext, making it susceptible to eavesdropping and tampering, which poses risks for sensitive information.

- Applications: HTTP is widely used for communication between web browsers and web servers, as well as for API calls and other network services.

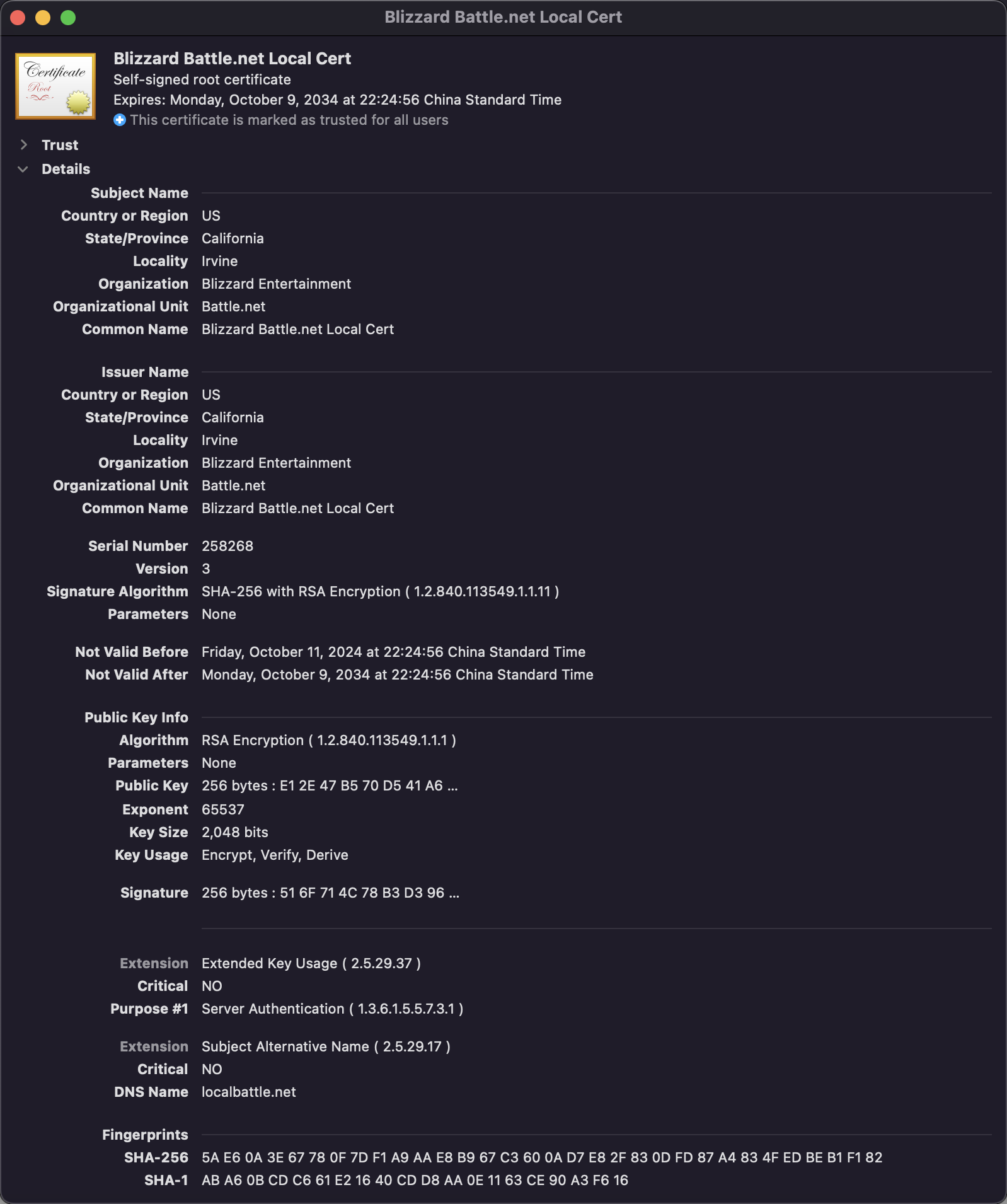

SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) and TLS (Transport Layer Security)

SSL (Secure Sockets Layer), originally developed by Netscape, has been succeeded by TLS (Transport Layer Security), standardized by IETF. TLS versions have evolved from TLS 1.0 to the latest TLS 1.3, improving security and performance with each iteration.

Working Principles, SSL/TLS ensures secure communication through several mechanisms:

- Encryption: Combines symmetric encryption (e.g., AES) and asymmetric encryption (e.g., RSA or ECDH) to ensure data confidentiality. During the handshake process, the client and server negotiate a shared secret (master key) used to encrypt subsequent communications.

- Authentication: Verifies the server’s identity using digital certificates issued by trusted third-party Certificate Authorities (CAs). These certificates contain public keys and other identifying information.

- Integrity: Prevents data tampering during transmission using Message Authentication Codes (MAC) or HMAC (Hash-based MAC).

- Handshake Protocol: A critical step in establishing a secure connection, involving parameter exchanges necessary for encrypted communication, such as selecting encryption algorithms and exchanging pre-master secrets.

- Record Protocol: Once the handshake is successful, all application data is packaged into TLS records for ransmission. Each record includes version numbers, lengths, types, encrypted payload data, and other control information.

Futhermore, TLS provides enhanced security features such as:

- Forward Secrecy: Modern key exchange algorithms like DHE and ECDHE provide forward secrecy, ensuring that even if long-term stored keys are compromised in the future, past sessions cannot be decrypted.

- Certificate Transparency: Increases transparency in certificate issuance and management, aiding in the timely detection and response to improperly issued certificates.

- OCSP Stapling: Allows the server to pass the latest certificate revocation status directly to the client, speeding up the handshake process and reducing load on CAs.

To reduce the overhead of full handshakes on every connection, TLS supports faster handshake methods like Session Tickets and Session IDs. These mechanisms allow resuming previous sessions without repeating the entire handshake process, accelerating connection establishment.

Here is an example of a SSL certificate from Blizard:

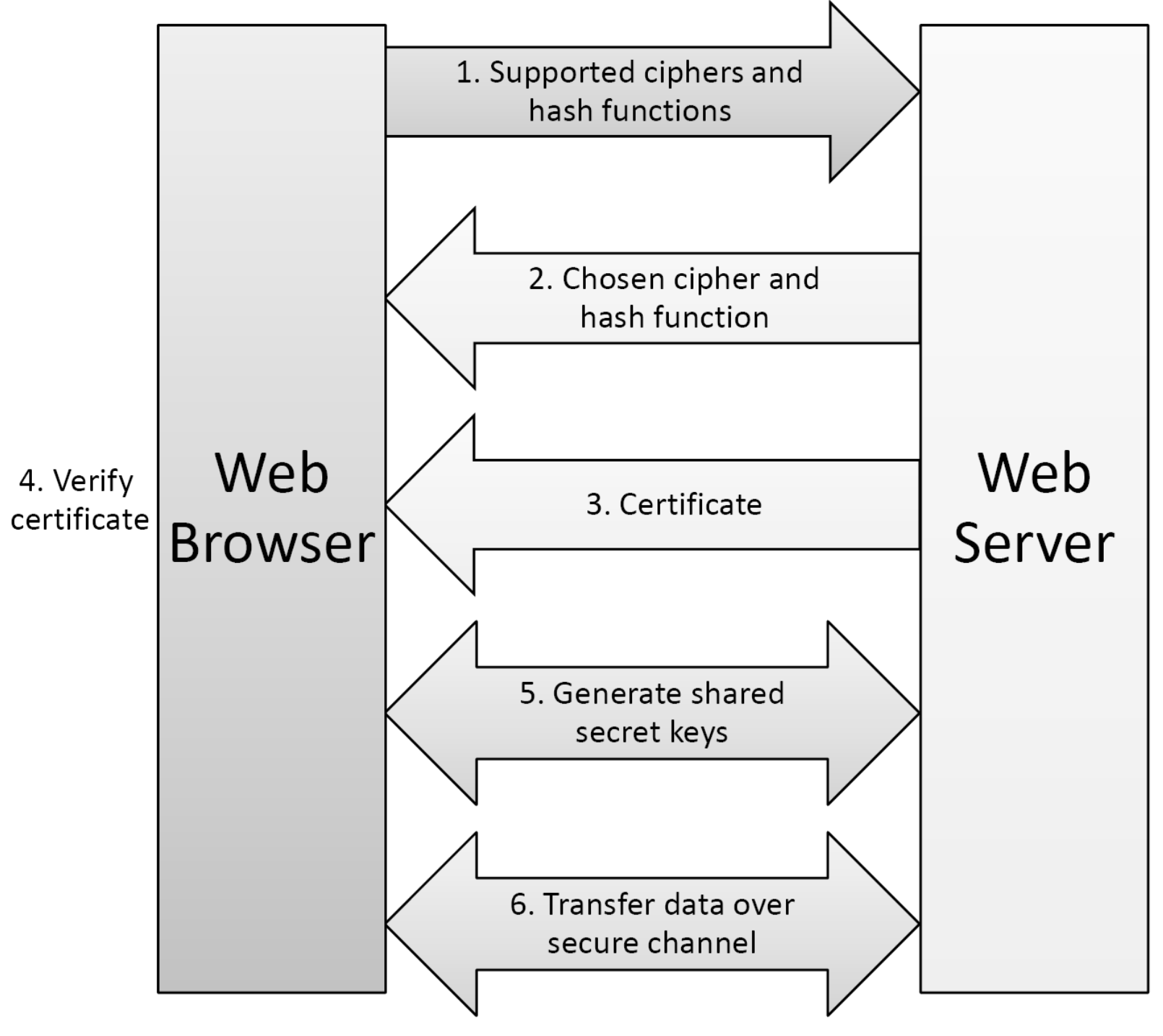

HTTPS (HyperText Transfer Protocol Secure)

HTTPS adds SSL/TLS to HTTP to provide encrypted communication and ensure data integrity. HTTPS typically uses port 443 and offers higher security and privacy protection compared to HTTP. The characteristics of HTTPS include:

- Encrypted Communication: Encrypts HTTP messages using SSL/TLS, preventing eavesdropping and tampering during data transmission. This involves combining symmetric and asymmetric encryption techniques.

- Authentication: Not only encrypts data but also verifies the server’s identity, allowing clients to confirm the server’s authenticity via digital certificates, thus preventing man-in-the-middle attacks.

- Integrity: Ensures data integrity, so even if data is intercepted, attackers cannot modify it without detection.

- Performance Overhead: Encryption and decryption consume computational resources, introducing additional performance costs compared to HTTP. However, modern hardware significantly mitigates this impact.

- SEO Advantage: Search engines favor HTTPS websites, considering them more secure and reliable, which can boost search rankings.

HTTPS is a secure and reliable communication protocol that provides enhanced security and privacy for web traffic. Servers can optionally instruct browsers to access the site exclusively via HTTPS using HSTS policies, enhancing security further.

The HTTPS handshake involves the TLS/SSL handshake, including:

- ClientHello: The client sends a ClientHello message containing supported TLS versions, cipher suites, random numbers, and possibly session IDs.

- ServerHello: The server selects a mutually supported cipher suite and responds with a ServerHello message, also containing a random number.

- Certificate Exchange: The server sends its digital certificate to the client, which contains the public key for verifying the server’s identity and subsequent key exchanges. ClientKeyExchange: The client generates a pre-master secret and sends it to the server, encrypted with the server’s public key.

- ChangeCipherSpec: Both client and server send ChangeCipherSpec messages indicating they will switch to using negotiated keys and encryption algorithms for communication. Finished: Both sides send Finished messages, encrypted with the new keys, to verify the successful completion of the handshake.

- Application Data Transmission: After the handshake, client and server communicate using the negotiated encryption parameters.

Although HTTPS remains a stateless protocol, web applications often use additional mechanisms to maintain session states across multiple requests. Methods include setting Cookies, using Session IDs, or Tokens (such as JWT), which pass state information between requests, enabling the application layer to track user sessions.

In summary, HTTPS provides enhanced security and privacy for internet communications, despite introducing some complexity and minor performance costs. In today’s increasingly security-conscious environment, HTTPS has become the standard configuration for network services.

Cookies, JWT, and Session Management

In modern web applications, maintaining user state and authentication information is crucial. Cookies and JSON Web Tokens (JWT) are three essential mechanisms used for this purpose.

Cookies

Cookies are small pieces of data sent by a server to a client’s browser, which then sends them back with every subsequent request to the same server. This allows the server to identify specific users.

- Working Principle:

- Setting Cookies: The server sets cookies using the Set-Cookie header in its HTTP response.

- Storing Cookies: Browsers store cookies based on attributes like path, domain, and expiration time.

- Sending Cookies: Browsers automatically include stored cookies in the headers of future requests to the same domain.

- Deleting Cookies: Cookies can be deleted by setting their expiration time to a past date or sending a Set-Cookie header with Max-Age=0.

- Security Features:

- HttpOnly: Prevents access via JavaScript, reducing XSS risks.

- Secure: Ensures cookies are only sent over HTTPS connections.

- SameSite: Limits cookie behavior in cross-site requests, helping prevent CSRF attacks.

- Use Cases:

- Authentication: Used to verify user identity and maintain session state.

- Personalization: Stores user preferences, such as language or theme.

- Analytics: Tracks user behavior and usage patterns.

JSON Web Tokens (JWT)

JWT is a compact and self-contained method for securely transmitting information between parties as a JSON object. It is commonly used for authentication and information exchange.

- Structure: A JWT consists of three parts separated by dots (.)

- Header: Contains metadata about the token, including the type and signing algorithm.

- Payload: Contains claims, such as user ID and permissions.

- Signature: Verifies the integrity of the token by signing the header and payload with a secret or private key.

- Workflow:

- Generating Token: After successful authentication, the server generates a JWT and sends it to the client.

- Storing Token: Clients store the JWT locally, often in local storage, session storage, or as an HttpOnly cookie.

- Sending Token: Clients include the JWT in the Authorization header of each request (

Authorization: Bearer <token>). - Verifying Token: The server parses and verifies the JWT’s signature and claims before processing the request.

- Advantages:

- Stateless: Reduces server load as no session data needs to be stored.

- Cross-Domain Support: Suitable for cross-origin requests.

- Easier Debugging: Self-descriptive tokens allow developers to inspect their contents.

- Disadvantages:

- Size: Larger than simple session IDs, especially with extensive payloads.

- Revocation Challenges: Harder to revoke or update once issued unless short-lived.

Session Management

Session management tracks user interactions across multiple requests, providing personalized services despite HTTP being stateless.

- Implementation:

- Cookie-Based Sessions: The server generates a unique Session ID and sends it to the client via Set-Cookie. The client includes this ID in subsequent requests.

- Token-Based Sessions: Similar to JWT but typically refers to short-lived, opaque tokens for brief session states. Session Storage:

- Server-Side: Store session data in memory, databases, or distributed caches (e.g., Redis) for scalability. Client-Side: Occasionally encode session data in URLs or hidden form fields, though this is less common due to security concerns.

- Security Practices:

- Regularly Refresh Session IDs to mitigate long-lived session hijacking risks.

- Secure Transmission: Always use HTTPS to send session identifiers.

- Limit Session Lifespan: Implement timeouts to automatically terminate idle sessions.

- Multi-Factor Authentication: Enhance security with additional verification steps.

| Feature | Cookie-Based Sessions | Token-Based Sessions (e.g., JWT) |

|---|---|---|

| Storage | Server-Side (Session data stored on server, session ID stored client-side in a cookie) | Client-Side (Token stored in local storage, session storage, or HttpOnly cookie) |

| Security | Vulnerable to CSRF if not properly configured; can mitigate XSS with HttpOnly and Secure flags |

Self-contained and tamper-proof, but vulnerable to token theft if not properly secured (e.g., using HTTPS and short expiration times) |

| Size | Generally smaller (only storing a session ID) | Larger due to payload (includes user claims and metadata) |

| Revocation | Easier (server can invalidate session data) | More difficult (requires blacklisting tokens or short-lived tokens) |

| Scalability | Potentially less scalable due to server-side storage requirements | More scalable as it reduces server load by being stateless |

| Stateless | Not stateless (server must store session data) | Stateless (server does not need to store session data) |

| Use Cases | General-purpose session management, tracking user sessions | Authentication, authorization, and information exchange in stateless applications |

Attack Scenarios and Countermeasures

In this section, we will explore some common web security attacks and provide countermeasures to protect against them.

Phishing Attacks

Phishing is a form of cyberfraud where attackers use fake emails, instant messages, or websites to obtain victims’ sensitive information such as usernames, passwords, and credit card details. This type of attack typically exploits social engineering principles to trick users into voluntarily disclosing personal information.

According to the Anti-Phishing Working Group (APWG) in its “Phishing Trends Reports,” approximately 45,000 unique phishing sites were detected monthly in 2009. This statistic highlights that phishing was a prevalent and serious issue at that time.

Attack Methods and Targets

The primary targets of these attacks include:

- Financial Services (e.g., Citibank)

- Payment Services (e.g., PayPal)

- Online Auction Platforms (e.g., eBay)

Phishing attacks typically involve a combination of deceptive communication methods and technical tactics to mask the true nature of malicious websites. Below is an integrated overview of the methods used in phishing attacks, highlighting the techniques employed to obscure URLs.

- Spoofed Web Page: Phishers create fake web pages that closely mimic legitimate sites, often targeting financial services (e.g., Citibank), payment platforms (e.g., PayPal), and online auction platforms (e.g., eBay). These spoofed pages are designed to trick users into entering their personal or financial information.

- Spam Emails: Malicious emails are crafted to appear as if they come from trusted entities. They contain links or attachments that lead users to these fake web pages. The goal is to exploit the trust users place in recognized brands and institutions.

- URL Obfuscation Techniques. The displayed URL is often different from the actual URL, making it difficult for users to recognize the target. URLs are constructed so that what appears in the browser’s address bar looks trustworthy, but the actual destination is a different, malicious site. For example, a URL might display

http://trusted.comwhile redirecting the user tomalicious.com. To further deceive users and evade detection, attackers employ various URL obfuscation methods:- URL Escape Character Attack: Exploiting vulnerabilities in older browsers like Internet Explorer, attackers use escape characters (

%01for SOH and%00for NULL) to hide parts of the URL. In the case ofhttp://trusted.com%01%00@malicious.com, the browser only showshttp://trusted.com, masking the redirection to the malicious site. - Unicode Attack (IDN Homograph Attack): By registering domain names with Unicode characters that visually resemble standard Latin letters, attackers can create domains that look identical to well-known websites. For instance, using Cyrillic “а” instead of Latin “a” can result in domains like

www.xn--pypal-4ve.com(Punycode representation), which appears almost indistinguishable from the real PayPal domain.

- URL Escape Character Attack: Exploiting vulnerabilities in older browsers like Internet Explorer, attackers use escape characters (

Countermeasures

To protect oneself from phishing attacks, users should adopt the following preventive measures:

- Direct URL Entry: Avoid clicking on links from untrusted sources; instead, enter the URL directly into the browser’s address bar.

- Check HTTPS Encryption: Ensure that visited sites use SSL/TLS encryption (i.e., URLs start with

https://). - Language and Format Awareness: Legitimate financial institutions and service providers generally do not request sensitive information via email. -** Install and Update Security Software**: Keep antivirus software and firewalls up-to-date to defend against known threats.

- Watch for Unusual Characters: Be wary of URLs containing complex encodings or unusual character combinations, which could indicate URL obfuscation.

Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)

Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) is a type of security vulnerability that allows attackers to inject malicious scripts into web pages viewed by other users. These scripts run in the user’s browser, potentially accessing cookies, manipulating Document Object Model (DOM) objects, and controlling what users see on the webpage. Despite being confined by the same-origin policy, which restricts scripts to interacting only with data from the same origin (protocol, domain, and port), XSS can still pose significant risks.

XSS vulnerabilities arise when web applications incorporate user inputs directly into web pages without proper sanitization or encoding. Common vectors for such inputs include:

- User comments

- Search queries

- Form submissions

If these inputs are not properly handled, they can carry malicious scripts that get executed when other users view the affected page.

Consider a scenario where Mallory discovers an XSS vulnerability on Bob’s website. She crafts a tampered URL exploiting this vulnerability and sends it to Alice via email, pretending it comes from Bob. When Alice clicks on this link while logged into Bob’s site, the malicious script executes in her browser, secretly stealing her confidential information and sending it to Mallory’s server.

Browser Architecture and Security: Multi-Process Isolation

In traditional single-process, multi-threaded browser architectures, all functionalities such as web page rendering, plugin execution, and user interface management are handled within a single process using multiple threads. While this design can enhance performance in some aspects, it also introduces significant security and reliability issues:

-

Security Weaknesses: In a single process, all threads share the same memory space and resources. If one thread has a vulnerability or is exploited by an attacker, the entire process (including other threads) becomes compromised. For example, malicious scripts can affect the entire browser session through one thread, potentially stealing sensitive information.

-

Poor Reliability: If one thread crashes (due to a problematic webpage or plugin), it can cause the entire browser process to crash, affecting all open pages. This not only degrades the user experience but can also lead to data loss.

Modern browsers like Google Chrome address these issues with a multi-process architecture that isolates different components into separate processes, preventing problems on one site from affecting others or the entire browser.

- Browser Process: Manages the user interface and system interactions, controlling the creation and destruction of other processes.

- Renderer Processes: Each tab typically runs in its own renderer process, handling web content rendering and JavaScript execution. If one tab crashes, it does not impact others.

- Plugin Processes: Handle third-party plugins, enhancing stability and security.

Through the use of multi-process architecture, browsers can address these issues:

- Security: Uses OS protection mechanisms to ensure different sites cannot easily interact, reducing the attack surface.

- Reliability: A crash in one website does not affect others.

Attack Methods

Types of Scripts Injected. Attackers can inject various types of scripting codes into web pages generated by a web application, including but not limited to:

- JavaScript: Often used with AJAX for dynamic content loading.

- VBScript

- ActiveX

- HTML: Malicious HTML tags can alter the structure of the page.

- Flash

Potential Threats, The threats posed by XSS attacks include:

- Phishing: Deceiving users into revealing sensitive information.

- Session Hijacking: Stealing session tokens to impersonate users.

- Modification of User Settings: Changing account configurations without user consent.

- Cookie Theft/Poisoning: Stealing or altering user cookies.

- False Advertising: Displaying misleading advertisements.

- Client-Side Code Execution: Executing arbitrary code on the user’s browser.

Countermeasures

Client-Side Defenses

- Proxy-Based Defense:

- Analyze HTTP traffic between the browser and web server.

- Detect and encode special HTML characters before rendering the page in the user’s browser (e.g., NoScript plugin for Firefox).

- Application-Level Firewall:

- Inspect HTML pages for hyperlinks that might lead to sensitive information leakage.

- Block harmful requests using predefined connection rules.

- Auditing System: Monitor JavaScript execution and compare operations against high-level security policies to detect malicious behavior.

Server-Side Defenses

- Input Validation and Sanitization: Ensure all user inputs are validated and sanitized before incorporating them into web pages. This includes escaping special characters and filtering out potentially harmful content.

- Content Security Policy (CSP): Implement CSP headers to define which sources of content are allowed to be loaded by the browser. This helps prevent the execution of unauthorized scripts.

- HTTPOnly Cookies: Set the HttpOnly flag on cookies to prevent access via client-side scripts, reducing the risk of cookie theft.

- Output Encoding: Encode output data before rendering it in web pages. This ensures that any injected scripts are rendered as plain text rather than executable code.

By understanding the principles behind XSS, recognizing the attack methods, and implementing robust defense mechanisms, developers and users can significantly reduce the risk of falling victim to XSS attacks. Educating users to recognize and avoid suspicious links is also crucial in maintaining web security.

Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF)

Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF or XSRF), also known as a one-click attack or session riding, is an attack that tricks the victim into submitting a malicious request. This type of attack exploits the trust a website has in a user’s browser.

The core effect of CSRF is transmitting unauthorized commands from a user who has logged into a website to the same site. The attack leverages the fact that browsers automatically attach cookies set by domain X to any request sent to domain X, even if the request originates from another domain.

A user logs into bank.com and forgets to log out. The session cookie remains in the browser. The user then visits another site that contains a hidden form like this:

<form name="F" action="http://bank.com/BillPay.php" method="POST">

<input type="hidden" name="recipient" value="badguy">

...

</form>

<script>document.F.submit();</script>

When this form is submitted, the browser sends the user’s authentication cookie with the request. As a result, the transaction is fulfilled without the user’s explicit consent.

Attack Method

- Social Network “Like”: Malicious sites could force users to “like” a page without their consent.

- Bank Transfer: Malicious sites could force users to transfer money to a chosen account without their consent.

- Email Spam: Malicious sites could force users to send spam emails to a chosen email list without their consent.

Countermeasures

Server-Side Defenses:

- Use of Cookies + Hidden Fields for Authentication

- Incorporate unpredictable, user-specific tokens (often called anti-CSRF tokens) in web forms.

- These tokens are validated on the server side when processing the form submission.

- An attacker forging a request would need to guess these hidden field values, which is practically impossible due to their unpredictability.

- Require POST Body to Contain Cookies

- Implement mechanisms where the body of the POST request must explicitly contain cookies.

- Since browsers do not automatically add cookies to cross-origin requests, a malicious script would need to add them manually.

- However, due to the Same-Origin Policy, the script does not have access to these cookies, preventing forgery.

- Double Submit Cookie Pattern

- Send a token via a cookie and also include it in the request body or URL.

- The server compares both tokens; if they match, the request is considered valid.

- Synchronizer Token Pattern

- Generate a unique token for each session or request and store it on the server.

- Embed this token in forms and verify it upon submission.

- This ensures that only requests originating from trusted sources are processed.

- Custom Request Headers

- Require custom headers for AJAX requests that cannot be set by browsers automatically.

- This adds an additional layer of verification since attackers cannot easily replicate these headers.

User-Side Best Practices:

- Log Off Before Using Other Sites

- Encourage users to log out of sensitive sites before navigating to other web pages.

- This reduces the window of opportunity for CSRF attacks.

- Selective Sending of Authentication Tokens

- Users can configure their browsers or use extensions to control when and where authentication tokens are sent.

- While this approach can disrupt normal browsing behavior, it significantly enhances security.

- Browser Security Extensions/Plugins: Recommend using browser extensions or plugins that provide additional protection against CSRF attacks.

Related Posts / Websites 👇

Comments