Operating System Guide Questions

This post contains a list of high level overview questions to help prepare for the OS exam.

Table of Contents

- Questions 🙋

- Question 1: What is a OS? What are the four major tasks performed by OS?

- Question 2: How could a system be designed to allow a choice of operating system from which to boot? What would the bootstrap program need to do?

- Question 3: What is the main advantage of the microkernel approach to system design? How do user programs and system services interact in a microkernel architecture? What are the disadvantages of using the microkernel approach?

- Question 4: Why does an operating system design, in general, use layered approach? Please state its advantages and disadvantages.

- Question 5: What is a process? What is a thread? Please compare them.

- Question 6: What resources are used when a thread is created?

- Question 7: What are the five states of a process in a computer system? Please describe the relationships of these five process states.

- Question 8: Describe the actions taken by a kernel to context-switch between processes.

- Question 9: Why does an operating system have both the user mode and the kernel mode for processes? What are the advantages and disadvantages of the design?

- Question 10: Please list and describe three major activities of the operating system with regard to memory management, and three major activities of the operating system with regard to secondary storage management.

- Question 11: Can the segmentation and paging mechanisms cooperate with each other? Please give your reasons.

- Question 12: What is a Thrashing? How to resolve this problem?

- Question 13: What is Table Lookaside Buffer (TLB)? How it works?

- Question 14: What are the major purposes of Table Lookaside Buffer (TLB)? How it works if the memory hierarchy includes L1, L2 and L3 caches?

- Question 15: What is Interrupt? What are its usages?

- Question 16: How to use interrupt and polling mechanisms to do process manipulation?

- Question 17: Why do we need Direct Memory Access (DMA) mechanism? How does DMA mechanism perform data transfer among memory and I/O devices?

- Question 18: How to use Memory Mapped I/O mechanism to perform file access operations?

- Question 19: Some file systems are good for small file manipulations while others are good for large file operations. How to design a file system that is good for both small and large file manipulations.

- Question 20: What are the advantages of the variant of linked allocation that uses a FAT to chain together the blocks of a file?

- Question 21: Explain the role of mmap mechanism. What’s the difference between MAP_SHARED and MAP_PRIVATE? When should the mechanism increase and decrease the reference counter of a file?

- Question 22: Discuss situations in which the least frequently used (LFU) page replacement algorithm generates fewer page faults than the least recently used (LRU) page-replacement algorithm. Also discuss under what circumstances the opposite holds.

- Question 23: Describe the Life Cycle of an I/O request.

Questions 🙋

Question 1: What is a OS? What are the four major tasks performed by OS?

An Operating System (OS) is a system software that manages computer hardware and software resources and provides common services for computer programs. It acts as an intermediary between users and the computer hardware. Without an OS, interacting with a computer would be much more complex, as all instructions would have to be given directly to hardware in a language the computer understands. The OS simplifies this interaction, making computers accessible to non-experts.

The four major tasks performed by an operating system include:

- Process Management: The OS handles the creation and termination of both user and system processes. It also oversees suspending and resuming processes, blocking or allowing their execution, and allocating necessary resources to these processes. This ensures multiple programs can run concurrently without interfering with each other.

- Memory Management: The OS manages the primary storage, RAM (Random Access Memory), ensuring that each process has enough memory space to operate and preventing conflicts between different processes. When physical memory is insufficient, the OS may use disk space as virtual memory.

- File System Management: The OS provides a structured method for storing files so users can easily save, find, retrieve, and update files. It manages how files are organized, stored, retrieved, updated, and what permissions they have for access. For more practical details, refer to xv6, xv6 docs and labs of mmap, bigfile management.

- Device Management: The OS controls and coordinates the use of various external devices (such as printers, scanners, etc.), ensuring they respond correctly to user requests. It communicates with hardware through device drivers, enabling hardware devices to be effectively used by applications.

Question 2: How could a system be designed to allow a choice of operating system from which to boot? What would the bootstrap program need to do?

Normally, the bootstrap program loads the operating system at boot time. One design in use is to make the bootstrap program load a separate program other than an OS kernel at boot time. This separate program is called a boot manager. The boot manager knows the names and locations of the different OSes installed on the computer, and can load them into memory and execute them as required. The boot manager is configurable, either at boot time or by a separate user-level program that can be run before a reboot. Linux uses a boot manager known as GrUB (Grand Unified Bootloader), so Linux users can boot into either Linux or Windows if they choose. The bootstrap program itself resides in hardware and thus cannot be changed. Because the bootstrap program is fixed, it always loads a program from a fixed location in secondary storage. Either the OS (in the case of a machine that has as single OS installed) or the boot manager (in case of a machine that offers a choice of OSes) resides at this fixed location.

Disclaimer: The answer to this question was obtained from Quizlet OS Chapter 2 Flash Cards.

Question 3: What is the main advantage of the microkernel approach to system design? How do user programs and system services interact in a microkernel architecture? What are the disadvantages of using the microkernel approach?

The main advantage of the microkernel approach to system design is its modularity and high reliability. In a microkernel architecture, only essential services for basic operation are implemented in the kernel, while all other services operate as separate processes in user space. This separation leads to several benefits:

- Modularity: Services can be added, removed, or updated independently without affecting the core system.

- Easier Maintenance: If a service fails, only that specific service is affected, rather than the entire system.

- Increased Flexibility: Services can be added or removed without affecting the rest of the system.

- High Reliability: If a service fails, it does not necessarily cause the entire system to crash, as failures are contained within the specific service.

- Fast Bootup: Due to small kernel size, booting the system is much faster than with a monolithic kernel, as the kernel does not need to be loaded from disk.

Interaction between User Programs and System Services: In a microkernel architecture, user programs interact with system services primarily through message-passing mechanisms. When a user program needs to access a service, it sends a message to the appropriate service process. The message contains the type of request and any necessary parameters. The service process receives the message, processes the request, and responds by sending a message back to the user program. This method enhances flexibility but introduces overhead due to crossing the boundary between user and kernel space.

In a traditional monolithic kernel architecture, the operating system services and functionalities are mostly integrated directly into the kernel. This means that user programs can interact with these in-kernel services directly via system call interfaces without requiring additional message-passing mechanisms.

Disadvantages of Using the Microkernel Approach: While offering significant advantages, the microkernel approach also has drawbacks:

- Performance Loss: Frequent message passing and context switching can lead to lower performance compared to monolithic kernels, as each inter-process communication involves transitions from user to kernel space and back.

- Increased Complexity: Ensuring correct message passing and synchronization among different services adds complexity to system design. Development and debugging become more challenging as errors can occur across multiple separated services rather than being centralized in one kernel.

- Resource Consumption: Each service running as an independent process consumes certain resources, potentially leading to higher resource usage overall.

Other approaches, such as the multithreaded kernel, can also be used to achieve similar functionality, but with different trade-offs:

- Monolithic Kernel:

- A monolithic kernel is the traditional design approach for an operating system kernel, where all operating system services—such as device drivers, file system management, network protocol stacks—are included and run within the kernel space. The advantage of this design is high efficiency because all operations are executed in kernel mode, reducing the overhead associated with switching between user mode and kernel mode.

- However, its disadvantages are also evident: since all services operate within the same address space, if one service crashes or has a flaw, it can affect the stability and security of the entire system.

- Hybrid Kernel:

- The hybrid kernel attempts to combine the benefits of both monolithic kernels and microkernels to achieve a balance between performance and modularity. In this architecture, certain core services remain in kernel space, while other services are moved into user space to run as separate processes.

- Such a design increases system stability (since not all services run in kernel space) while retaining a degree of performance benefits. Windows NT, macOS, and some versions of Linux utilize a hybrid kernel design.

- Exokernel:

- An exokernel represents a more radical design philosophy that provides only a minimal hardware abstraction layer, performing almost no resource management or protection itself but delegating these responsibilities to library operating systems (LibOS) at the application level. This means applications can directly control hardware resources, potentially offering higher performance and flexibility.

- Despite providing high flexibility and potential performance gains, the exokernel also increases programming complexity, as developers must handle many low-level details themselves, which can be quite challenging for non-experts.

Question 4: Why does an operating system design, in general, use layered approach? Please state its advantages and disadvantages.

Operating system design often employs a layered approach as a structured strategy to organize its functionalities and services into multiple layers. Each layer builds upon the one below it, providing services to the layer above. This architecture allows each layer to focus on specific sets of functions, simplifying the design, implementation, and maintenance of the system.

| Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|

| Simplifies debugging and system verification by isolating layers. | Can introduce additional overhead due to layer-to-layer communication. |

| Enhances modularity, making it easier to update or replace components. | May lead to reduced performance due to abstraction layers. |

| Allows for clear separation of responsibilities among system components. | Complexity in precise definition and enforcement of layer boundaries. |

Also see a blog on AspiringYouths that discusses the layered approach for general system design: AspiringYouths - Advantages and Disadvantages of Layered Approach To System Design

Question 5: What is a process? What is a thread? Please compare them.

- A process is the fundamental unit of resource allocation and scheduling in an operating system. It represents an instance of a running program, with its own independent address space, memory, data stack, and other auxiliary data. Processes are isolated from each other; the crash of one process does not directly impact others.

- A thread is an execution unit within a process, sometimes referred to as a lightweight process. A single process can contain multiple threads, which share the same resources such as memory and file descriptors. Unlike processes, switching between threads has lower overhead because they share most of their context information.

| Characteristic | Process | Thread |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | An instance of a running program. | An execution path within a process. |

| Resources | Has its own separate memory space, file descriptors, etc. | Shares the resources (e.g., memory) of the parent process, but has its own stack, registers, etc. |

| Isolation | Highly isolated; a crash in one process typically does not affect others. | Less isolated within the same process; a thread crash can cause the entire process to crash. |

| Communication | Inter-Process Communication (IPC) is more complex, requiring special mechanisms (pipes, message queues, etc.). | Intra-process communication is simpler, as threads can directly access shared data. |

| Creation Overhead | Creating a process is more expensive, as the OS needs to allocate new address spaces and other resources. | Creating a thread is less expensive, as it does not need to duplicate most of the parent process’s resources. |

| Context Switching | Context switching costs are higher, involving saving and restoring more state information. | Context switching costs are lower, as only a smaller amount of state information needs to be saved and restored. |

| Scheduling | Scheduled by the operating system scheduler. | Can be scheduled by either the operating system or user-level libraries. |

| Multitasking | On a single-core CPU, processes appear to run concurrently over time. On multi-core CPUs, they can run in parallel. | More suitable for lightweight parallel or concurrent tasks within the same application. |

| Usage | Suitable for running completely independent applications. | Suitable for task decomposition within the same application to improve responsiveness and resource utilization. |

Also see my blogs on Ray - Threads and Ray - Processes

Question 6: What resources are used when a thread is created?

When a thread is created, the operating system allocates certain resources to ensure the new thread can operate correctly. Although threads share most of the resources of their parent process (such as address space, open files, and signal handling settings), each thread still requires some independent resources. Specifically:

- Stack Space: Each thread has its own stack for storing function calls, local variables, and return addresses. The size of the stack can be configured based on application needs and typically defaults to a relatively small fixed value.

- Register Set: Each thread has its own set of registers, including the program counter (PC), instruction register (IR), and other general-purpose registers. These registers hold key information about the thread’s execution state.

- Thread Control Block (TCB): The TCB is a data structure used by the OS to manage threads. It contains the thread identifier, scheduling information (priority, time slice), state (ready, running, waiting), and pointers to other relevant data structures.

- Memory Allocation: While threads share the address space of the process, additional memory allocation may be required in some cases, such as for thread-private data structures or dynamically allocated objects.

- Synchronization Objects: To coordinate work among multiple threads, synchronization mechanisms like mutexes, condition variables, or semaphores might be created to ensure threads safely access shared resources.

- Other Resources: Depending on the specific functionality of the thread, other types of resources might be involved, such as network connections, database handles, etc.

In summary, while threads are lighter than processes, creating a thread still consumes certain system resources, primarily stack space, register sets, thread control blocks, and related synchronization objects.

Also see my blog on Ray - Threads

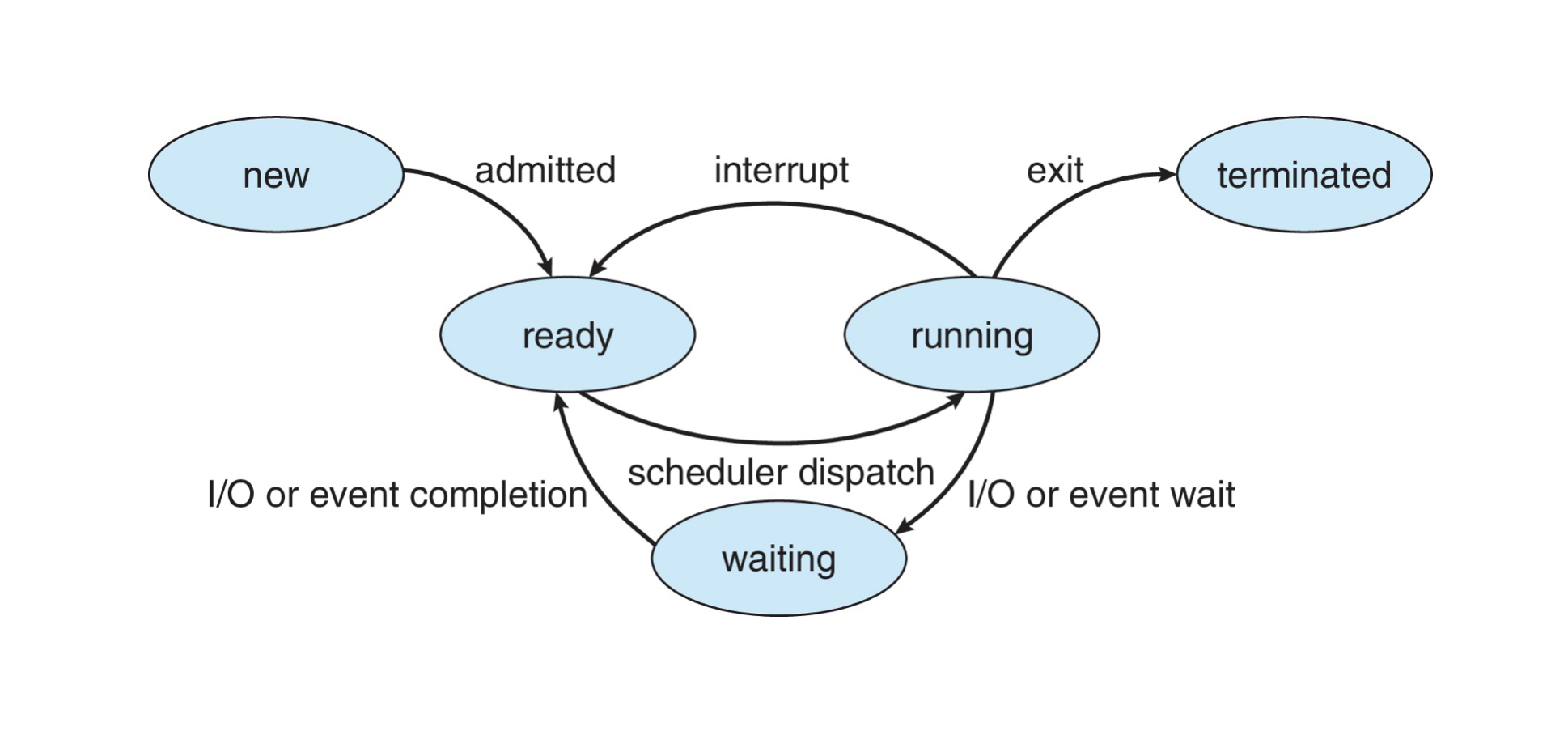

Question 7: What are the five states of a process in a computer system? Please describe the relationships of these five process states.

In a computer system, a process can be in one of the following five states during its lifecycle:

- New: When a new process is created, it enters the New state. At this stage, the operating system allocates necessary resources for the process and records its information in the process table, but the process is not yet ready to execute.

- Ready: Once initialization is complete and all required resources are ready, the process transitions to the Ready state. Here, the process is prepared to run but awaits CPU time to begin execution. Processes in the Ready state are placed in one or more queues, awaiting selection by the scheduler.

- Running: When the scheduler selects a Ready process and assigns it to the CPU for execution, it moves into the Running state. This is the only state where the process actually executes instructions. On a single-core processor, only one process can be in the Running state at any given moment, whereas multi-core processors allow multiple processes to run concurrently.

- Blocked (or Waiting): If a running process needs to wait for an event to occur (such as I/O completion, user input, semaphore, etc.), it transitions from the Running state to the Blocked state. In this state, the process cannot proceed until the awaited event occurs. For example, after initiating a disk read/write request, the process might enter the Blocked state until data transfer is complete.

- Terminated (or Exit): When a process completes its tasks or encounters an unrecoverable error and ends, it enters the Terminated state. In this state, the operating system reclaims all resources used by the process and clears all associated information. Terminated processes no longer participate in system scheduling and execution.

Transitions between these states occur in a controlled and deterministic manner, ensuring that processes are managed efficiently and that all resources are properly allocated and released.

- New to Ready: After creation and initialization, a process moves from the New state to the Ready state.

- Ready to Running: When the scheduler selects a Ready process and assigns it CPU time, the process transitions from the Ready state to the Running state.

- Running to Blocked: If a running process needs to wait for some external event (like I/O), it changes from the Running state to the Blocked state until the event is completed.

- Blocked to Ready: Once the reason for blocking is resolved (such as I/O completion), the process returns to the Ready state, waiting for its next scheduling opportunity.

- Running to Terminated: Upon completing its work or encountering an unrecoverable error, a process directly enters the Terminated state, where the OS recovers its resources.

- Ready to Terminated: Although less common, under certain special circumstances, such as system shutdown or forced termination, a process can transition directly from the Ready state to the Terminated state.

Also see my blog on Ray - Processes

Question 8: Describe the actions taken by a kernel to context-switch between processes.

When an operating system needs to switch from one process to another, it must save the state of the current process (its context) so that it can resume execution later and load the state of the next process to execute. This procedure is known as a context switch. Below are the typical steps taken by the kernel during a context switch:

- Save the Current Process’s Context: The kernel first saves all state information of the currently running process, including the contents of CPU registers (such as the program counter, instruction register, general-purpose registers, etc.), memory management information (page tables), and any other relevant data. This information is usually saved in the process’s Process Control Block (PCB).

- Update Scheduling Information: The kernel updates the scheduling information for the current process, such as changing its state from “Running” to “Ready” or “Blocked” and adjusting its priority or other scheduling parameters as needed.

- Select the Next Process: The scheduler chooses the next process to execute based on certain algorithms (like First-Come-First-Served, Shortest Job Next, Round Robin, etc.). This may involve evaluating the priority, waiting time, and other factors of ready processes.

- Load the New Process’s Context: Once the new process is selected, the kernel loads its context, restoring all previously saved state information from its PCB back into the CPU registers and other relevant locations. This includes setting the program counter to point to the start address of the new process code and reconfiguring the Memory Management Unit (MMU) to reflect the new process’s address space.

- Begin Execution of the New Process: Finally, the kernel hands control over to the new process, allowing it to continue executing as if it had never been interrupted.

- Handle Synchronization and Resource Management: In some cases, a context switch also involves handling synchronization issues (such as locks, semaphores) and resource management (such as file descriptors, network connections) to ensure the new process can safely access required resources without conflicting with the old process.

By following these steps, the kernel achieves smooth switching between processes, ensuring efficient operation of multitasking systems. Each context switch introduces some overhead, so optimizing scheduling strategies and minimizing unnecessary switches are crucial for enhancing system performance.

This structured explanation outlines the key actions taken by the kernel during a context switch, emphasizing the importance of preserving and restoring process states efficiently.

Also see my blog on Ray - Processes

Question 9: Why does an operating system have both the user mode and the kernel mode for processes? What are the advantages and disadvantages of the design?

Operating systems introduce User Mode and Kernel Mode to provide enhanced security and stability while efficiently managing hardware resources. These two modes define different levels of privileges for processes during execution:

- User Mode: Programs running in user mode do not have direct access to hardware or system resources. They can only request privileged operations through system calls to the operating system. This ensures that regular applications cannot directly modify critical system data or hardware states, thereby enhancing system stability and security.

- Kernel Mode: Code executing in kernel mode has the highest level of privilege, allowing direct access to all hardware resources and memory regions. The core parts of the operating system and drivers typically run in this mode. Due to their high privileges, these components must be carefully written to prevent errors from causing system-wide crashes.

Advantages

- Enhanced Security: User mode restricts direct access by applications to hardware and core system functionalities, reducing the likelihood of damage caused by malware or programming errors.

- Improved Stability: By separating non-privileged tasks from privileged ones, even if a program in user mode fails, it does not directly impact the kernel or other critical system components, thus improving overall system stability.

- Simplified Debugging and Support: Errors are isolated within specific modes, making issues easier to locate and fix. For instance, if a user program crashes, it won’t affect other user programs or the kernel itself.

Disadvantages

- Performance Overhead: Each transition from user mode to kernel mode for a system call introduces additional overhead, including saving the current context, switching modes, and restoring the context, which can reduce system responsiveness.

- Increased Complexity: Designing and implementing two distinct privilege levels adds complexity to the system. Developers need to understand and correctly handle transitions between modes, increasing programming difficulty.

- Potential Bottlenecks: Frequent switches between the two modes, especially for applications requiring rapid responses, can become performance bottlenecks. Additionally, poor design can lead to deadlocks or other synchronization issues.

In summary, the design of user mode and kernel mode is a crucial feature in operating system architecture, offering higher levels of security and stability at the cost of some performance challenges and increased complexity. Proper configuration of these modes can maximize their benefits while minimizing adverse effects.

Also see my blog on Ray - Processes

Question 10: Please list and describe three major activities of the operating system with regard to memory management, and three major activities of the operating system with regard to secondary storage management.

Three Major Activities in Memory Management

- Memory Allocation and Deallocation: The operating system is responsible for allocating required memory space to processes and reclaiming it when the process ends or no longer needs these resources. This involves dynamically allocating and releasing memory blocks to ensure efficient use of limited physical memory resources. Various algorithms (such as Best Fit, First Fit) are used to decide how to allocate free memory blocks to requesting processes.

- Address Translation: To protect each process’s independence and simplify programming models, the OS implements virtual memory mechanisms. It uses hardware support (like MMU, Memory Management Unit) to translate program-used virtual addresses into actual physical addresses. This translation not only enhances security in multitasking but also allows programs to access a larger address space than the actual physical memory, known as virtual memory.

- Page Replacement and Swapping: When available physical memory is insufficient, the OS must decide which pages should be moved out of memory to make room for new or active pages. Page replacement algorithms (such as LRU, Least Recently Used) are used to select suitable pages for replacement. Additionally, entire processes can be swapped out to a swap area on disk (Swapping), making more memory available for higher-priority processes.

Three Major Activities in Secondary Storage Management

- File System Management: The OS provides an abstract interface for managing file and directory structures. This includes creating, deleting, reading, writing files, as well as renaming and moving files and directories. The file system also maintains metadata about files (such as permissions, timestamps) and ensures data consistency and integrity.

- Storage Allocation and Deallocation: Similar to memory management, the OS manages the allocation and reclamation of storage space on disk. It handles partitioning, volume, and file allocation strategies on disk to ensure efficient use of disk space. When files are deleted or updated, the OS adjusts the storage layout on disk accordingly to avoid fragmentation issues.

- Data Protection and Recovery: The OS employs various measures to protect data stored in secondary storage from hardware failures, software errors, or other anomalies. Examples include implementing backup mechanisms, logging, snapshot features, and redundant storage technologies (such as RAID). Moreover, the OS must provide effective recovery tools and services to quickly restore data in case of data loss or corruption.

These structured descriptions outline key activities in both memory and secondary storage management, highlighting the essential roles played by the operating system in ensuring efficient and secure resource utilization.

Question 11: Can the segmentation and paging mechanisms cooperate with each other? Please give your reasons.

Segmentation and paging mechanisms can indeed cooperate with each other, and this combination is known as a segmented paging system. In such a system, memory management combines the logical advantages of segmentation with the physical management benefits of paging.

Characteristics of Segmentation

- Logical Partitioning: Segmentation allows programs to be divided into multiple logical parts, such as code segments, data segments, stack segments, etc. Each segment has its own address space and can grow or shrink independently.

- Sharing and Protection: Different processes can share certain segments, like the code segments containing library functions. Meanwhile, each segment can have different access permissions, providing a protection mechanism.

Characteristics of Paging

- Fixed-Sized Pages: Paging divides the virtual address space into fixed-size blocks called pages, while physical memory is also divided into equally sized blocks called frames.

- Reducing External Fragmentation: Because pages and frames are the same size, there is no external fragmentation; all unused memory is internal fragmentation, which can be managed through appropriate page replacement algorithms.

How Segmentation and Paging Collaborate

When segmentation and paging are used together:

- Multi-Level Address Translation: Each segment has its own segment table, with entries pointing to a page table. The page table then maps logical pages to physical frames. Thus, a logical address requires two-level table lookups (first the segment table, then the page table) to obtain the corresponding physical address.

- More Flexible Memory Management: Segmentation provides the ability to logically separate different types of code and data, while paging ensures efficient use of memory by reducing fragmentation issues.

- Simplified Sharing: Segmentation can simplify the sharing of code and data because it can simply point multiple processes to the same segment table entry.

- Enhanced Protection: Segmentation allows setting access permissions for each segment, thereby enhancing system security.

Practical Application Example

For example, in modern operating systems like Linux, a hybrid memory management approach that incorporates both segmentation and paging is adopted. The Linux kernel uses a minimal number of segments (usually only two: user space and kernel space) and then implements paging within these segments. This method maintains the efficiency brought by paging while taking advantage of the protection and isolation features provided by segmentation.

Question 12: What is a Thrashing? How to resolve this problem?

Thrashing is a phenomenon in computer operating systems’ memory management that occurs in paging systems. It happens when the system spends an excessive amount of time swapping pages into and out of memory, rather than executing useful instructions. In this state, CPU utilization drops significantly while disk I/O activity increases, leading to degraded overall performance.

Causes of Thrashing

- Large Working Set: If a process’s working set (the set of pages it accesses over some interval of time) is larger than the available physical memory, the process will frequently generate page faults.

- Too Many Multiprogrammed Processes: When too many processes are running concurrently and each process does not have enough allocated physical memory frames to hold its working set, thrashing can occur.

Solutions for Resolving Thrashing

- Reduce the Number of Concurrent Processes: Lowering the number of processes running concurrently gives more physical memory to each process to accommodate their working sets.

- Adjust Page Size: Increasing the page size can reduce the number of pages, potentially lowering the frequency of page replacements. However, this should be decided based on specific application scenarios and hardware support.

- Use More Intelligent Page Replacement Algorithms: Advanced page replacement algorithms like LRU (Least Recently Used), Optimal, etc., can help predict which pages should be kept or replaced more effectively.

Question 13: What is Table Lookaside Buffer (TLB)? How it works?

The Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB) is a hardware cache used in modern computer systems to improve the efficiency of address translation. The TLB stores recently used mappings from virtual addresses to physical addresses. When the processor needs to translate a virtual address into a physical one, it first checks whether this mapping information is already present in the TLB.

How TLB Works

-

Address Translation: In operating systems that use paging, each process has its own page table that records the mapping between the process’s virtual address space and physical memory. Each time the CPU generates a virtual address, the OS must look up the page table to find the corresponding physical address.

-

TLB Hit: If the translation for this virtual address is found in the TLB (a TLB hit), the physical address can be obtained directly from the TLB without needing to access the slower main memory page table, thus greatly speeding up address translation.

-

TLB Miss: If the virtual address is not in the TLB (a TLB miss), the page table must be accessed to complete the address translation, and typically the newly acquired mapping is added to the TLB for faster access in the future.

-

Replacement Policy: Because the capacity of the TLB is limited, when inserting new entries, old ones might need to be removed. For this purpose, the TLB uses a replacement algorithm, such as Least Recently Used (LRU), to decide which entry should be replaced.

-

TLB Flush: Upon certain events, like context switches or pages being swapped out of memory, the operating system may request the contents of the TLB to be flushed to ensure the mapping information in the TLB remains up-to-date.

Advantages of TLB

- Performance Improvement: By reducing the number of accesses to main memory, it speeds up address translations.

- Power Saving: Reduces the frequency of main memory accesses, contributing to lower overall power consumption.

In short, a translation lookaside buffer (TLB) is a memory cache that stores the recent translations of virtual memory to physical memory. It is used to reduce the time taken to access a user memory location. It can be called an address-translation cache. It is a part of the chip’s memory-management unit (MMU).

Question 14: What are the major purposes of Table Lookaside Buffer (TLB)? How it works if the memory hierarchy includes L1, L2 and L3 caches?

The major purposes of the Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB) include:

- Accelerating Address Translation: The TLB caches recently used mappings from virtual addresses to physical addresses, thereby reducing the number of memory accesses required to look up page tables. This can significantly speed up address translations.

- Improving System Performance: By decreasing the frequency of main memory accesses, it not only increases the speed at which CPU instructions are executed but also reduces overall system latency.

- Reducing Power Consumption: As a result of fewer accesses to main memory, there is a reduction in energy consumption.

In modern computer architectures, alongside the TLB, we have multiple levels of cache (such as L1, L2, and L3), forming a hierarchical memory system. In this architecture, the workflow of the TLB is as follows:

- CPU Generates Virtual Address: When the CPU needs to access data or instructions, it generates a virtual address.

- TLB Lookup: The system first queries the TLB to see if there is an existing mapping for the virtual address to a physical address (a TLB hit). If such a mapping exists, the physical address is used directly for access; if not (a TLB miss), the process moves on to the next step.

- Multi-Level Cache Lookup: In case of a TLB miss, the system attempts to find the required data or instruction in the fast but smaller L1 cache first. If the L1 cache does not contain the item, the search proceeds through the progressively slower but larger L2 and L3 caches.

- Access Memory and Update TLB: If all cache levels fail to provide the needed data or instruction, the system will eventually have to access main memory. Once the data or instruction is retrieved from main memory, its copy is usually placed in the closest level of cache (like L1), and the corresponding mapping from virtual to physical address is added to the TLB to facilitate faster access to the same data or instruction in the future.

In summary, within a multi-level cache memory hierarchy, the role of the TLB is to ensure that the address translation process remains as efficient as possible, maintaining low latency even within complex memory systems.

Question 15: What is Interrupt? What are its usages?

An interrupt is a hardware mechanism in computers that allows external devices or specific events within the system to break into the CPU’s normal instruction flow as it executes programs. When an interrupt occurs, the CPU pauses its current work, saves its state, and transfers control to an interrupt service routine (ISR) to handle the event. After handling the interrupt, the CPU returns to where it left off and resumes normal execution.

Interrupts can be categorized into two main types:

- Hardware Interrupts: Triggered by external hardware devices, such as pressing a key on the keyboard, moving a mouse, or when a network adapter receives a packet.

- Software Interrupts: Actively triggered by the operating system or applications through executing specific instructions, used for requesting services from the operating system, like creating processes or opening files.

The primary usages of interrupts include but are not limited to:

- Improving Response Time: Enabling the computer to respond quickly to external events, such as user inputs or sensor signals, without having to constantly poll the status of these devices.

- Enabling Multitasking: Assisting the operating system in managing multiple concurrently running tasks, allowing each task to get a slice of CPU time at appropriate moments.

- Error Handling: Used for detecting and responding to system errors, such as division by zero, out-of-bounds memory access, and other exceptional conditions.

- Synchronizing Operations: Coordinating communications between hardware components operating at different speeds, ensuring they correctly pass information back and forth.

- Timer Functionality: Leveraging periodic interrupts generated by timers to implement timing, delays, and other functionalities.

In summary, the interrupt mechanism is crucial for the efficient operation of modern computing systems. It enhances system flexibility and efficiency, improves reliability, and supports real-time performance.

Question 16: How to use interrupt and polling mechanisms to do process manipulation?

In an operating system, interrupts and polling are two mechanisms used for detecting changes in the state of external devices or receiving signals from hardware. They can also be applied to process control and scheduling. Here’s how these two mechanisms can be used for process manipulation:

Interrupt Mechanism: An interrupt is a method of asynchronous event handling where, upon occurrence of a specific event such as user input, arrival of a network packet, or timer expiration, the CPU pauses its current task and executes a dedicated piece of code called an Interrupt Service Routine (ISR). After completing the ISR, the CPU returns to the task it was executing before the interruption.

Process Manipulation Using Interrupts: When an interrupt occurs, the operating system may create new processes or adjust the state of existing ones as needed. For instance, a keyboard interrupt might prompt the OS to start a new text editor process; or, an interrupt indicating that a disk read/write operation has completed can transition a process waiting on that I/O from a blocked state to a ready state.

Polling Mechanism: Polling is a synchronous event-handling method where the CPU periodically checks if certain conditions are met, such as querying device registers to see if new data is available. If the condition is satisfied, appropriate actions are taken; otherwise, the checking continues until the condition is met.

Process Manipulation Using Polling: In polling mode, the operating system might regularly check whether a resource is available and decide whether to wake up processes waiting for that resource based on the outcome of the checks. For example, a process could be waiting for a network interface to receive packets, and the OS uses polling to monitor the status of the network interface, setting the process to a runnable state once new data arrives.

Choosing Between the Two Mechanisms: The choice between using interrupts or polling depends on the specific application scenario. Generally, interrupts are better suited for low-frequency but time-sensitive tasks because they can respond immediately when an event occurs. Polling, on the other hand, is more appropriate for high-frequency checking scenarios, although it can lead to higher CPU overhead, it simplifies programming logic and reduces hardware complexity.

Question 17: Why do we need Direct Memory Access (DMA) mechanism? How does DMA mechanism perform data transfer among memory and I/O devices?

We need the Direct Memory Access (DMA) mechanism because it significantly enhances the performance and efficiency of computer systems. Without DMA, the CPU would have to handle each data transfer request personally, which typically involves reading data from an I/O device into a register and then writing it into memory. This approach not only consumes a large number of CPU cycles but also adds latency to the system.

The Role of DMA Mechanism: DMA allows for direct data transfers between I/O devices and system memory without involving the CPU. By doing so, the CPU can focus on other tasks, such as running user applications or handling other interrupt requests. Additionally, DMA can reduce competition between the CPU and the bus, as the DMA controller can take over the bus control to perform data transfers when the CPU is not using the bus.

How DMA Works

- Initialization: When a data transfer is needed, the operating system configures the DMA controller by specifying how much data to transfer, the source address (usually the buffer in an I/O device), the destination address (usually a memory address), and the direction of the transfer (read or write).

- Starting the Transfer: Once all settings are done, the DMA controller begins the data transfer. It requests bus control either when the CPU is idle or according to a predetermined priority scheme and carries out the actual data transfer.

- Completion of Transfer: After the data transfer is complete, the DMA controller sends an interrupt signal to the CPU, informing it that the data transfer has ended. At this point, the CPU can check the status and continue with other tasks.

Data Transfer Modes

DMA supports several different modes of data transfer, including:

- Burst Mode: Transfers as much data as possible in one go until the entire block is transferred. This mode is suitable for rapid transfers of large blocks of data.

- Cycle Stealing Mode: Only transfers a small amount of data at a time to minimize the impact on the CPU. This mode is appropriate for small amounts of data or applications requiring high real-time performance.

- Transparent Mode: Attempts to perform data transfers when the CPU is not using the bus to ensure minimal impact on the CPU.

The DMA mechanism does indeed require the use of the system bus to perform data transfers

Question 18: How to use Memory Mapped I/O mechanism to perform file access operations?

Memory-Mapped I/O (MMIO) allows the CPU to access memory and I/O devices through the same address space. Under this mechanism, the registers of I/O devices are mapped into the CPU’s address space, so these devices can be operated using standard memory read/write instructions.

When discussing the use of MMIO for file access operations, we’re actually referring to a feature provided by the operating system called Memory-Mapped Files. This feature makes the contents of a file or part of a file accessible as if they were loaded into memory, allowing programs to read and write large files more efficiently by avoiding explicit data copying steps that occur in traditional file I/O.

To use memory-mapped files, you generally follow these steps:

- Create or Open File: First, you need to create a new file or open an existing one via a system call.

- Map File to Memory: Then, use a system call (such as the

mmapfunction on Unix/Linux, orCreateFileMappingandMapViewOfFilefunctions on Windows) to map the file or a portion of it into the process’s virtual address space. - Access File Content: Once the file is mapped, you can perform read or write operations directly on the mapped region as if you were manipulating ordinary memory.

- Synchronize Modifications (Optional): If modifications have been made to the mapped region, you may need to ensure that these changes are written back to the file on disk. This is typically handled automatically by the operating system, but in some cases, you might need to manually call a function like

msyncto ensure this. - Unmap the Region: When you no longer need to access the file, you should unmap the region (e.g., with the

munmapfunction) to release resources. - Close the File: Finally, close the file descriptor or handle.

Using memory-mapped files can simplify code and improve performance for certain types of file access patterns, especially when dealing with large files.

Question 19: Some file systems are good for small file manipulations while others are good for large file operations. How to design a file system that is good for both small and large file manipulations.

Designing a file system that can efficiently handle both small and large files is challenging because small files and large files have significantly different storage and access patterns. Small files tend to be numerous with individually smaller sizes, whereas large files are fewer but require potentially contiguous storage for efficient read/write performance. To create a file system that excels at handling both types of files, consider the following strategies:

- Hybrid Block Sizes: Use varying block sizes to accommodate different file types. Smaller blocks reduce internal fragmentation for small files, while larger blocks improve transfer efficiency for large files.

- Indirect Index Structures: Provide indirect indexing structures (such as UNIX’s inodes or Windows NTFS’s B+ trees) for large files to manage non-contiguous storage effectively.

- Metadata Optimization: Optimize the metadata structure of the file system to ensure rapid lookup and updating of file information. For example, cache recently used metadata or keep frequently accessed metadata in memory.

- Small File Consolidation: Reduce excessive disk seek times caused by many small files by considering packing multiple small files into larger blocks for storage, maintaining a mapping table to track each small file’s location.

- Preallocate Space: Allow applications to preallocate the required disk space for files, reducing fragmentation issues as files grow.

- Adaptive Algorithms: Dynamically adjust filesystem parameters based on file access patterns. For instance, if heavy small-file operations are detected, temporarily change certain configurations to prioritize these operations.

- Log-Structured File Systems: Employ log-structured file systems (LFS) to minimize fragmentation and accelerate write operations. LFS writes new data and metadata sequentially, which helps boost performance for large file operations.

- Compression and Deduplication: Apply file-level compression and deduplication techniques, which not only save storage space but also reduce I/O load, especially when dealing with large files containing much redundant content.

Question 20: What are the advantages of the variant of linked allocation that uses a FAT to chain together the blocks of a file?

The File Allocation Table (FAT) is a data structure used in computer file systems to manage the allocation of space on a disk or other storage device. It was originally designed by Microsoft in 1977 for early versions of MS-DOS and later became one of the most commonly used file systems in personal computers.

The primary function of FAT is to track the location of files on the disk and the space they occupy. Specifically:

-

Recording Cluster Chains: Each file may consist of multiple data blocks, called clusters, which can be scattered across different locations on the disk. FAT maintains a table that records the position of each cluster and indicates where the next cluster in the chain is located. This allows the operating system to read the entire file by following this chain.

-

Free Space Management: In addition to tracking used clusters, FAT is responsible for marking which clusters are free, meaning available for storing new data. When saving new files or expanding existing ones, the operating system consults the FAT to locate available free clusters.

-

Error Recovery: Some versions of FAT implement redundancy mechanisms, such as keeping two copies of the FAT (the main FAT and a backup FAT), so information can be recovered from the other copy if one gets corrupted.

-

Support for Various File Systems: Over time, different versions of FAT have emerged, including FAT12, FAT16, and FAT32, each supporting different maximum volume sizes and individual file sizes. For example, FAT32 can support partitions up to 2TB in size (depending on the operating system) with individual files as large as 4GB.

The simplicity of the FAT file system has led to its widespread use in various portable storage devices, such as USB drives and SD cards, because nearly all modern operating systems can read and write this format.

Using a File Allocation Table (FAT) to chain together the blocks of a file is a variant of linked allocation that offers several advantages:

- Efficient Sequential Access: The FAT records the location of the next cluster for each cluster, which allows files to be read sequentially without additional indirect lookups. This structure is very efficient for file read/write operations in sequential access patterns.

- Reduced Fragmentation: Compared to contiguous allocation, a FAT system does not require all blocks of a file to be stored in consecutive locations on disk. Thus, even if the disk becomes highly fragmented, files can continue to grow as long as there’s available space.

- Simple Deletion and Expansion: When deleting a file, it’s only necessary to mark the corresponding FAT entries as free; when expanding a file, find new free clusters and update the linking information in the FAT. Such operations are relatively simple and fast.

- Support for Random Access: Although initially designed for sequential access, random access to any position within a file can also be achieved by traversing the FAT from the root directory or the starting cluster of the file.

- Better Fault Tolerance: Some versions of FAT (like FAT32) include redundant copies of the FAT, so if the primary table is damaged, data can be recovered from the backup, improving the robustness and reliability of the system.

- Strong Compatibility: The FAT format is widely used across various operating systems and devices due to its simplicity and ease of implementation. For example, USB drives, SD cards often use FAT file systems to ensure cross-platform compatibility.

- Optimization for Small Files: For smaller files, FAT can optimize by allocating fewer large clusters, thereby reducing overhead while maintaining good performance.

The FAT-based linked allocation method thus provides a balance between simplicity, efficiency, and functionality, making it suitable for many applications where these factors are important.

Question 21: Explain the role of mmap mechanism. What’s the difference between MAP_SHARED and MAP_PRIVATE? When should the mechanism increase and decrease the reference counter of a file?

The Role of the mmap Mechanism: The mmap (memory-mapped file) mechanism is a method for mapping files or other objects into a process’s address space. By using mmap, applications can access file data directly in memory without resorting to traditional system calls like read and write for I/O operations. This not only improves performance but also simplifies the programming interface since file contents can be read from and written to as if they were regular memory.

- MAP_SHARED: When the

MAP_SHAREDflag is used, any modifications made to the mapped region are immediately reflected in the underlying file, and these changes are visible to all processes that map the same file. This means that if one process modifies content in a shared mapping, all other processes mapping the same file will see those changes. - MAP_PRIVATE: In contrast,

MAP_PRIVATEcreates a private copy of the mapping where modifications do not affect the original file. Instead, when the first write attempt is made to the region, a “copy-on-write” (COW) occurs. The operating system creates a copy of the page for the current process, ensuring that changes do not impact other processes or the file itself.

Increasing and Decreasing the File Reference Counter: For mmap, when a file is mapped, the kernel typically increments the file’s reference counter to ensure that even if the user closes the file descriptor, the file won’t be deleted or its metadata changed as long as there are still mappings held by processes. When the mapping is removed (for example, by calling munmap), the reference counter is correspondingly decremented. Once the reference count drops to 0, indicating no processes need this file anymore, it becomes safe to release associated resources or allow operations such as file deletion.

Question 22: Discuss situations in which the least frequently used (LFU) page replacement algorithm generates fewer page faults than the least recently used (LRU) page-replacement algorithm. Also discuss under what circumstances the opposite holds.

Situations Where LFU Generates Fewer Page Faults Than LRU: The Least Frequently Used (LFU) page replacement algorithm can generate fewer page faults than the Least Recently Used (LRU) under certain circumstances. Here are some scenarios where this might occur:

- Repetitive Access Patterns: If a program’s access pattern includes a significant amount of repetition, with some pages being accessed frequently and others rarely, LFU will tend to retain the frequently used pages, thereby reducing page faults.

- Periodic Workloads: For workloads that exhibit periodic behavior, such as data processing tasks that heavily access specific pages at fixed intervals, LFU can adapt better to this pattern because it takes into account the long-term frequency of page usage, not just recent usage.

- Locality in Multi-Level Cache Systems: In a complex storage hierarchy with multiple cache levels, each having different access characteristics, LFU can help maintain good locality for hot data in higher-level caches, thus reducing the overall page fault rate.

Circumstances Where LRU Generates Fewer Page Faults Than LFU: However, there are other scenarios where LRU may outperform LFU

- Sequential or Near-Sequential Access: For applications that scan memory regions in an almost linear fashion, such as database queries or video players reading files, LRU typically performs better. In these cases, pages recently accessed are likely to be accessed soon again, so keeping them in memory is advantageous.

- Short-Term Locality: If an application exhibits strong short-term locality, meaning it focuses on accessing a set of pages for a short period before moving on to another set, LRU can quickly adapt to this change by always retaining the most recently accessed set of pages, which helps minimize page faults.

- Non-Deterministic Access Patterns: When a program’s access pattern is highly random and unpredictable, LRU tends to offer better performance because it considers only recent history rather than long-term history, making it more responsive to sudden changes.

In summary, the choice between page replacement strategies depends on the characteristics of the workload and the behavior patterns of the applications. Ideally, a good page replacement algorithm should balance well across different workloads and dynamically adjust its behavior based on real-world conditions.

LRU algorithm selects the pages that have not been accessed for the longest period of time to be evicted. LFU prioritizes evicting the pages that have been accessed the least since they were loaded.

Question 23: Describe the Life Cycle of an I/O request.

The lifecycle of an I/O request describes the process from initiation, processing to completion of a device request. This process involves multiple levels, including the application layer, the operating system kernel, and the hardware level. Below are the main steps in the lifecycle of an I/O request:

- Application Initiates Request: An application issues a read or write request to the operating system via system calls (such as

readorwrite). - System Call Interface: The application’s request reaches the operating system kernel through the system call interface where it is translated and subjected to preliminary checks, such as verifying permissions and validating parameters.

- File System Operations: If the request involves the file system, the operating system locates the file’s position on the disk and may need to update metadata of the file system, like inode information.

- Buffer Management: To improve efficiency, the operating system typically maintains a buffer or cache in memory to store recently accessed data. If the requested data is already in the cache, it can be returned directly to the application without further action; otherwise, proceed to the next step.

- Device Scheduling: The operating system passes the I/O request to the appropriate driver which is responsible for interacting with the specific hardware. This step might involve queuing to wait for the device to become available or optimizing the order of requests according to certain algorithms.

- Actual I/O Operation: The driver sends commands to the hardware controller to perform the actual data transfer. For a disk, this could mean moving the head to the correct position and starting to read or write data.

- Interrupt Handling: Once the hardware has completed its operation, it generates an interrupt to notify the CPU. The CPU responds to the interrupt by calling the corresponding Interrupt Service Routine (ISR), which informs the operating system that the data is ready or has been successfully written.

- Completion and Return Results: Once all data has been correctly processed, the operating system notifies the application that the operation is complete and provides any necessary results or status information.

- Cleanup: Finally, the operating system performs some cleanup work, such as releasing resources and updating internal structures.

This lifecycle ensures that I/O operations are managed efficiently and effectively, providing a bridge between user applications and hardware devices.

Related Posts / Websites 👇

Comments