Agent Architecture

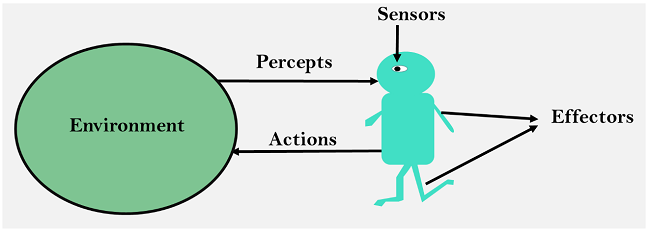

Agent architecture is a software design for an intelligent agent. It is a concrete implementation of the abstract agent structure, which consists of perception, state, decision, and action. An agent architecture defines key data structures, operations on data structures, and control flow between operations. It is a crucial component of an AI system, as it directly influences the performance of the system. This post provides a comprehensive discussion of agent architecture in Lecture 5 of the SC4003 course in NTU.

Table of Contents

- Development of the Agent Architecture

- Symbolic Reasoning Agents

- Reactive Agents

- Hybrid Architectures

Development of the Agent Architecture

Before going detailed into the architecture, let’s take a look at the development history of an agent architecture. I believe it will help us to better understand the concept of agent architecture. The history of agent architecture can be divided into three stages:

Symbolic Reasoning Agents (1956–1985)

In the early days of artificial intelligence, from approximately 1956 to 1985, agents were predominantly designed as symbolic reasoning systems. This period was heavily influenced by developments in logic, cognitive science, and computer science, leading researchers to believe that intelligence could be fully captured through explicit symbolic manipulation. In these agents, knowledge about the world was meticulously encoded using formal logical structures, such as first-order predicate logic, and actions were determined through systematic logical inference. Classical planning systems, such as STRIPS and the General Problem Solver (GPS), exemplified this approach by attempting to map out sequences of actions based on explicit models of the environment. Symbolic reasoning agents offered high degrees of interpretability and theoretical rigor, excelling in domains where complete, accurate world models could be constructed and manipulated. However, their limitations became increasingly apparent when applied to real-world scenarios. These agents were fragile in the face of incomplete or noisy data, struggled with dynamic and uncertain environments, and often suffered from intractable computational demands due to the complexity of logical inference. As the gap widened between the theoretical potential of symbolic AI and its practical performance, dissatisfaction with purely symbolic approaches grew, paving the way for new paradigms.

- Core idea: Intelligence is based on explicit symbolic reasoning and formal logic.

- Knowledge representation: Agents use structured logical forms (e.g., predicate logic) and reason using inference engines.

- Strengths: Highly interpretable; strong in well-structured, static environments.

- Weaknesses: Fragile with incomplete/noisy data; slow in dynamic, real-world settings; computationally intensive.

- Outcome: Growing dissatisfaction with purely symbolic methods due to practical limitations.

Reactive Agents Movement (1985–Present)

In reaction to the evident shortcomings of symbolic reasoning agents, the mid-1980s witnessed the rise of the reactive agents movement, led most notably by Rodney Brooks and his colleagues. This new school of thought argued that intelligence does not necessarily require internal symbolic models or complex deliberation but can emerge from direct interactions with the environment. Reactive agents eschewed internal representations altogether, instead relying on tightly coupled perception-action loops to generate behavior. Brooks’ Subsumption Architecture, a pioneering framework in this movement, proposed organizing behaviors into layers, with lower layers handling simple, reflexive responses and higher layers coordinating more complex actions. Crucially, reactive agents demonstrated remarkable robustness, flexibility, and speed, enabling them to operate effectively in unpredictable, noisy, and dynamic settings where traditional symbolic agents failed. Rather than planning out detailed strategies, reactive agents simply responded appropriately to current sensory inputs, leading to surprisingly sophisticated behavior through the interaction of simple rules. Nonetheless, while reactive architectures excelled at real-time responses and adaptability, they struggled to perform tasks requiring long-term planning, goal-directed reasoning, or the synthesis of information over extended periods. Thus, although they addressed critical flaws of symbolic systems, reactive agents introduced their own limitations, especially when applied to complex or strategic domains.

- Core idea: Intelligence emerges from direct perception-action links without internal symbolic models.

- Architecture: Simple behavior modules interact; layers prioritize immediate environmental responses (e.g., Subsumption Architecture).

- Strengths: Robust, fast, and adaptive in dynamic, unpredictable environments.

- Weaknesses: Poor at long-term planning, goal management, and abstract reasoning.

- Outcome: Effective for real-time tasks, but insufficient for complex decision-making.

Hybrid Architectures (1990–Present)

Recognizing that both symbolic reasoning and reactive behavior have unique strengths and weaknesses, researchers in the 1990s began to propose hybrid architectures that aimed to combine the best of both worlds. These architectures were typically structured into multiple layers, with reactive mechanisms operating at the lower levels to ensure rapid, context-sensitive responses to environmental changes, while higher levels employed symbolic reasoning and planning capabilities to handle complex, long-term decision-making tasks. One influential model of this era was the TouringMachines architecture, which integrated reactive control, planning, and monitoring layers into a cohesive system. Similarly, frameworks such as InteRRaP and 3T explored different methods of coordinating reactive and deliberative processes. Hybrid agents benefited from the ability to respond swiftly to immediate stimuli while maintaining the capacity for high-level reasoning, allowing them to tackle more sophisticated and dynamic environments than either purely symbolic or purely reactive agents could manage alone. However, designing effective hybrid systems posed significant challenges, particularly in harmonizing the potentially conflicting behaviors arising from different layers and ensuring that the system remained coherent and efficient under varying conditions. Despite these difficulties, hybrid architectures remain a dominant paradigm in modern AI agent design, reflecting a mature understanding that intelligent behavior in complex environments demands both immediate reactivity and strategic foresight.

- Core idea: Combine reactive and symbolic reasoning to leverage the strengths of both.

- Architecture: Multi-layered systems—lower layers handle rapid reactions, upper layers perform planning and reasoning.

- Strengths: Balance between real-time responsiveness and long-term, strategic thinking.

- Weaknesses: Complexity in integrating and coordinating different layers; potential internal conflicts.

- Outcome: Became the dominant model for intelligent agents in complex environments.

Symbolic Reasoning Agents

The classical approach to building agents is to view them as a particular type of knowledge-based system. This paradigm is known as symbolic AI. We define a deliberative agent or agent architecture to be one that:

- contains an explicitly represented, symbolic model of the world

- makes decisions (for example about what actions to perform) via symbolic reasoning

If we aim to build an agent in this way, there are two key problems to be solved:

- The transduction problem: that of translating the real world into an accurate, adequate symbolic description, in time for that description to be useful for decision making in vision, speech understanding, and learning.

- The representation/reasoning problem: that of how to symbolically represent information about complex real-world entities and processes, and how to get agents to reason with this information in time for the results to be useful.

Most researchers accept that neither problem is anywhere near solved. Underlying problem lies with the complexity of symbol manipulation algorithms in general: many (most) search-based symbol manipulation algorithms of interest are highly intractable. Because of these problems, some researchers have looked to alternative techniques for building agents. However, we will introduce some of the more popular symbolic reasoning agents in following subsections.

Deductive Reasoning Agents

The base idea of Deductive Reasoning Agents to use logic to encode a theory stating the best action to perform in any given situation. To formalize this idea, the following definition is often used:

- $\rho$: be this theory, typically a set of rules.

- $\Delta$: be a logical database that describes the current state of the world.

- $Ac$: be the set of actions the agent can perform.

- $\phi$: be the action intention proposition.

- $\Delta \vdash_{\rho} \phi$: mean that $\phi$ can be proved from $\Delta$ using $\rho$.

Given a set of rules $\rho$, a logical database $\Delta$, and a set of actions $Ac$, a Deductive Reasoning Agent will first try to find an action explicitly prescribed by the rules. If no such action is found, it will try to find an action not explicitly excluded. If no such action is found, the agent will return null.

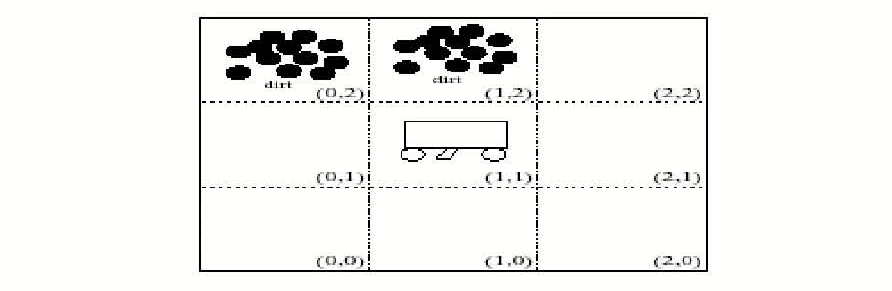

To better understand this idea, let’s take a look at the following example, The Vacuum World. The goal is for the robot to clear up all dirt:

We can use $3$ domain predicates to solve problem:

- $In(x, y)$ agent is at $(x, y)$

- $Dirt(x, y)$ there is dirt at $(x, y)$

- $Facing(d)$ the agent is facing direction $d$

And possible actions are: ($turn$ here means turn right)

\[Ac = \{turn, forward, suck\}\]Then write down all rules:

\[\begin{align*} In(0,0) \wedge Facing(north) \wedge \neg Dirt(0,0) & \implies Do(forward) \\ In(0,1) \wedge Facing(north) \wedge \neg Dirt(0,1) & \implies Do(forward) \\ \vdots \end{align*}\]Using these rules (plus other obvious ones), starting at (0, 0) the robot will clear up dirt. However, we still need to consider:

- How to convert video camera input to $Dirt(0, 1)$?

- Decision making assumes a static environment: calculative rationality.

- decision making using first-order logic is undecidable.

Typical solutions are:

- weaken the logic.

- use symbolic, non-logical representations.

- shift the emphasis of reasoning from run time to design time.

Agent-Oriented Programming

AOP, short for Agent-Oriented Programming, is a brand new programming paradigm proposed by Yoav Shoham in 1990. Shoham proposes that future programs should not be just calls between objects, but interactions between agents. Each agent is like an independent intelligent entity, with its own intentions, beliefs, and commitments, and can autonomously perceive the environment, make decisions, and execute actions.

AOP is a new programming paradigm based on a societal view of computation.

The key idea of AOP can be discribed as follows:

- No longer simply controlling the process or data, but modeling the psychological state of agents: Each agent has its own internal state (beliefs, commitments, intentions). Programmers can directly use these mental concepts to describe the behavior of agents, rather than hard-coded rules.

- The interaction between agents is similar to the behavior between individuals in society: Instead of simply calling functions, the agent sends a message, makes a commitment, and updates a belief update. The whole system is more like a society than a bunch of machines.

- More natural expression of complex, autonomous, and asynchronous systems: Especially suitable for describing systems that require autonomy, reactivity, and sociality, such as: Multi-Agent Systems (MAS), Distributed AI, Autonomous Robot Teams.

After AOP was proposed, specific implementation was needed, thus leading to the birth of the two typical early systems: AGENT0 and PLACA.

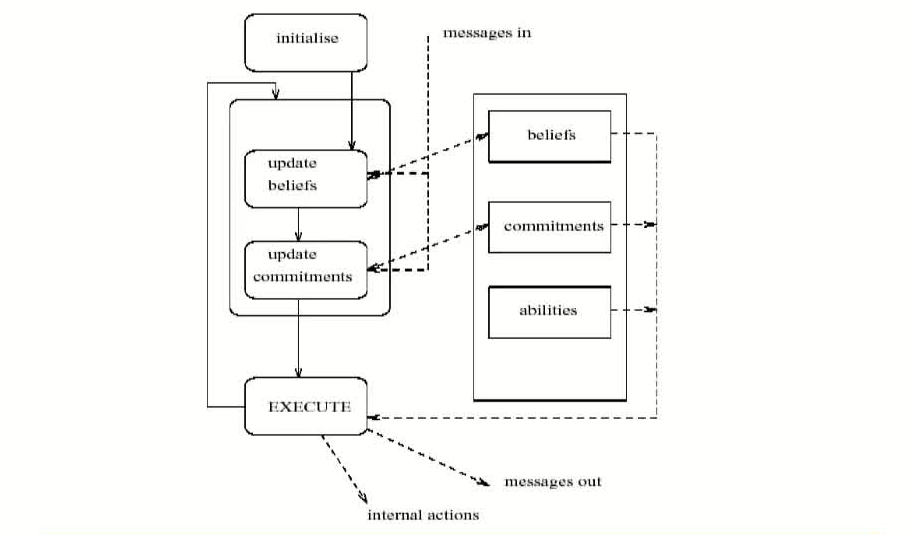

AGENT0 is implemented as an extension to LISP invented by Shoham. It is the first programming language truly based on the AOP concept. Each agent in AGENT0 has 4 components:

- a set of capabilities (things the agent can do)

- a set of initial beliefs

- a set of initial commitments (things the agent will do)

- a set of commitment rules

The key component, which determines how the agent acts, is the commitment rule set. Each commitment rule contains a message condition,a mental condition, and an action.

During each agent cycle: The agent evaluates incoming messages against the message condition and checks its own beliefs against the mental condition. If both conditions are satisfied, the rule is activated, and the agent commits to the specified action by adding it to its commitment set.

Action here may be an internally executed computation, or sending messages. Messages are constrained to be one of three types, requests to commit to action, unrequests to refrain from actions, and informs which pass on information. Following figure shows the work flow principle of AGENT0:

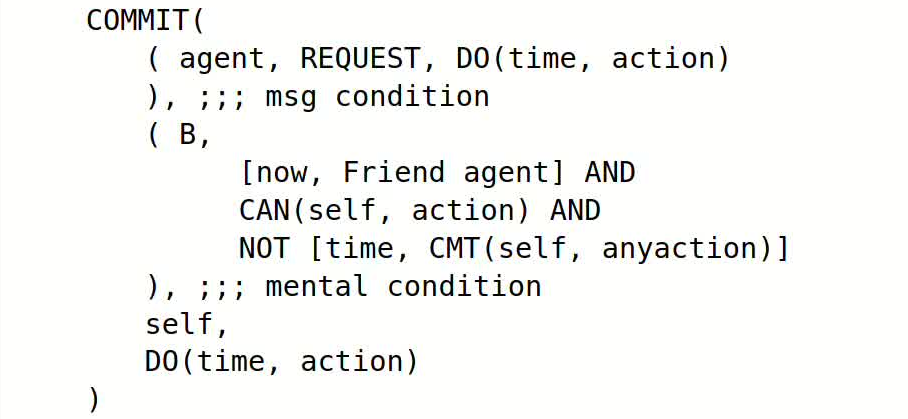

Then, let’s see an example of commitment rule:

This rule may be paraphrased like this, if I receive a message from agent which requests me to do action at time, and I believe that:

- agent is currently a friend

- I can do the action

- At time, I am not committed to doing any other action then commit to doing action at time

AGENT0 provides support for multiple agents to cooperate and communicate, and provides basic provision for debugging. It is, however, a prototype, that was designed to illustrate some principles, rather than be a production language. A more refined implementation was developed by Thomas, for her 1993 doctoral thesis. Her Planning Communicating Agents (PLACA) language was intended to address one severe drawback to AGENT0, the inability of agents to plan, and communicate requests for action via high-level goals. Agents in PLACA are programmed in much the same way as in AGENT0, in terms of mental change rules.

Practical Reasoning

Practical reasoning is reasoning directed towards actions, which is the process of figuring out what to do. It is distinguished from theoretical reasoning, since theoretical reasoning is directed towards beliefs.

Practical reasoning is a matter of weighing conflicting considerations for and against competing options, where the relevant considerations are provided by what the agent desires/values/cares about and what the agent believes. (Bratman, 1990)

Human practical reasoning consists of two activities:

- deliberation: deciding what state of affairs we want to achieve, the output of deliberation are intentions

- means-ends reasoning: deciding how to achieve these states of affairs

Notice that intentions in the context of practical reasoning are much stronger than mere desires:

My desire to play basketball this afternoon is merely a potential influencer of my conduct this afternoon. It must vie with my other relevant desires [. . . ] before it is settled what I will do. In contrast, once I intend to play basketball this afternoon, the matter is settled: I normally need not continue to weigh the pros and cons. When the afternoon arrives, I will normally just proceed to execute my intentions. (Bratman, 1990)

The basic idea of means-ends reasoning is to give an agent representation of goal/intention to achieve, actions it can perform the environment. And have it generate a plan to achieve the goal. Essentially, this is automatic programming. Plan is a sequence (list) of actions, with variables replaced by constants.

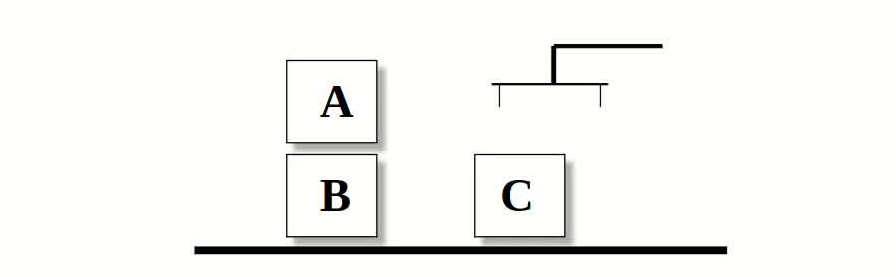

The core question is to find a way to represent: Goal to be achieved, State of environment, Actions available to agent, and Plan itself. We will illustrate the techniques with reference to the blocks world, which contains a robot arm, 3 blocks (A, B, and C) of equal size, and a table-top.

To represent this environment, need an ontology:

| Predicate | Description |

|---|---|

| $On(x, y)$ | obj $x$ on top of obj $y$ |

| $OnTable(x)$ | obj $x$ is on the table |

| $Clear(x)$ | nothing is on top of obj $x$ |

| $Holding(x)$ | arm is holding $x$ |

Here is a representation of the blocks world like the figure above:

\[\begin{array}{l} Clear(A) \\ On(A, B) \\ OnTable(B) \\ OnTable(C) \end{array}\]We will use the closed world assumption: anything not stated is assumed to be false. The goal can be formally stated as the formula:

\[OnTable(A) \wedge OnTable(B) \wedge OnTable(C)\]Actions are represented using a technique that was developed in the STRIPS planner. Each action has following components, and each of them may contain variables:

- name: which may have arguments.

- pre-condition list: list of facts which must be true for action to be executed.

- delete list: list of facts that are no longer true after action is performed.

- add list: list of facts that are true after action is performed.

An example of an action is: The stack action occurs when the robot arm places the object $x$ it is holding is placed on top of object $y$. The action is represented as:

\[\begin{align*} & \mathit{Stack}(x, y)\\ \text{pre } &\mathit{Clear}(y) \wedge \mathit{Holding}(x)\\ \text{del } &\mathit{Clear}(y) \wedge \mathit{Holding}(x)\\ \text{add } &\mathit{ArmEmpty} \wedge \mathit{On}(x, y) \end{align*}\]Deliberation begins by trying to understand what the options available to you are. Then choose between them, and commit to some. The chosen options are defined as intentions. This is a high-level explanation of deliberation. For more details, the deliberate function can be decomposed into two distinct functional components:

- option generation: in which the agent generates a set of possible alternatives; Represent option generation via a function, options, which takes the agent’s current beliefs and current intentions, and from them determines a set of options (these are so called desires).

- filtering: in which the agent chooses between competing alternatives, and commits to achieving them. In order to select between competing options, an agent uses a filter function.

The pseudo-code for control flow is as follows:

\[\begin{align*} &B := B_0;\\ &I := I_0;\\ &\text{while $True$ do}:\\ &\quad \text{get next percept } \rho;\\ &\quad B := brf(B, \rho);\\ &\quad D := options(B, I);\\ &\quad I := deliberate(B, I, D);\\ &\quad \pi := plan(B, I);\\ &\quad execute(\pi);\\ &\text{end while} \end{align*}\]where $B$ is the agent’s current beliefs, $I$ is the agent’s current intentions, $D$ is the agent’s current desires, and $\pi$ is the agent’s current plan.

Reactive Agents

There are many unsolved (some would say insoluble) problems associated with symbolic AI. These problems have led some researchers to question the viability of the whole paradigm, and to the development of reactive architectures. Although united by a belief that the assumptions underpinning mainstream AI are in some sense wrong, reactive agent researchers use many different techniques.

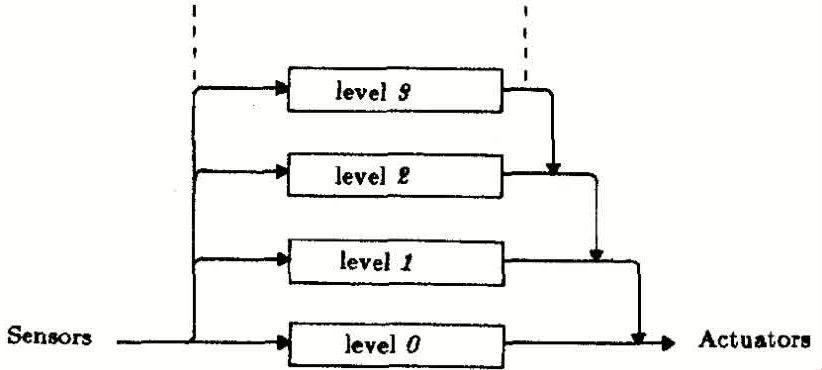

The Subsumption Architecture

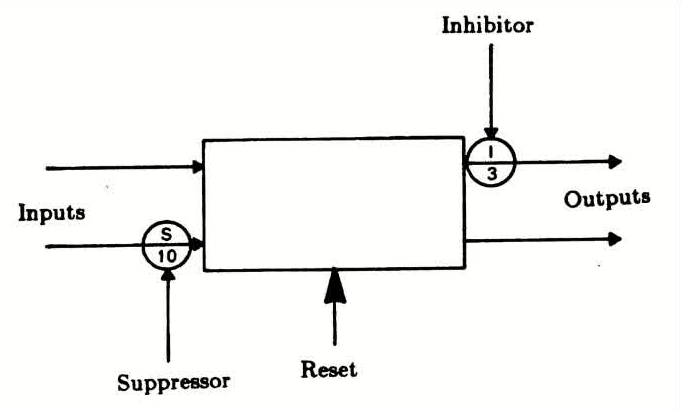

The Subsumption Architecture is a layering methodology for robot control systems, and also a parallel and distributed method for connecting sensors and actuators in robots. Each layer is made up of connected, simple processors - Augmented Finite State Machines. The most important aspect of these FSMs are: Outputs are simple functions of inputs and local variables; and inputs can be suppressed and outputs can be inhibitated. This function allows higher levels to subsume the function of lower levels. Lower, therefore, still function as they would without the higher levels.

In traditional symbolic reasoning agents, decision-making relies heavily on maintaining an internal model of the real world. These agents construct explicit, detailed representations of their environment using structured symbolic data, which must be continuously updated through communication between subsystems and synchronization of shared memory. Such an approach assumes that internal knowledge must mirror the external world as accurately as possible. However, this model-centric strategy introduces significant computational overhead, vulnerability to outdated information, and communication bottlenecks, especially in dynamic, uncertain environments where the world changes faster than the internal model can adapt.

Rodney Brooks’ subsumption Architecture offers a radical departure from this paradigm by rejecting the need for an internal world model altogether. Instead, Brooks proposed that “the world really is a rather good model of itself,” suggesting that agents should directly sense and react to the real environment without constructing abstracted internal representations. In subsumption systems, individual subsystems do not communicate with each other via explicit messages or shared memory; rather, they interact indirectly through the changes they observe in the environment. This design allows agents to maintain highly accurate, real-time awareness with minimal computational cost, enabling them to respond quickly and robustly to environmental changes without the risk of model obsolescence.

By using the real world as the medium of communication and source of truth, Subsumption-based agents achieve a level of reactivity and adaptability that traditional symbolic agents often struggle to match. In Brooks’ view, computation-heavy internal modeling is unnecessary for intelligent behavior; instead, intelligent systems should emerge from simple, decentralized modules that continually sense and act upon the immediate state of the world. This philosophy reflects a broader shift in AI from centralized, deliberative architectures toward decentralized, embodied intelligence, where complex behavior arises not from intricate planning but from the dynamic interaction with the environment itself.

| Traditional Symbolic Reasoning Agents | Brooks’ Subsumption Architecture |

|---|---|

| Maintain an internal model of the world | Rejects the need for an internal world model |

| Require free communication and shared memory between subsystems | Subsystems sense the real world directly instead of communicating internally |

| High computational overhead to update models | No extra computation needed to keep models accurate or synchronized |

| Risk of internal models becoming outdated in dynamic environments | Communication via Real World |

Brooks’ Behavior Languages

Brooks has put forward three theses:

- Intelligent behavior can be generated without explicit representations of the kind that symbolic AI proposes.

- Intelligent behavior can be generated without explicit abstract reasoning of the kind that symbolic AI proposes.

- Intelligence is an emergent property of certain complex systems.

He identifies two key ideas that have informed his research:

- Situatedness and embodiment: ‘Real’ intelligence is situated in the world, not in disembodied systems such as theorem provers or expert systems.

- Intelligence and emergence: ‘Intelligent’ behavior arises as a result of an agent’s interaction with its environment. Also, intelligence is ‘in the eye of the beholder’; it is not an innate, isolated property.

Brooks’ subsumption architecture is a hierarchical control system consisting of simple behaviors, each of which “competes” to control the agent. Lower layers represent more primitive behaviors (e.g. obstacle avoidance) and have precedence over higher layers. The system is computationally simple yet can accomplish tasks that would be impressive in symbolic AI systems.

Advantages and Disadvantages

The advantages of the interactive architecture are obvious: simplicity, economy, computational tractability, robustness against failure, and elegance.

But still have following shortcomings:

- Agents without environment models must have sufficient information available from local environment

- If decisions are based on local environment, how does it take into account non-local information (i.e., it has a short-term view)

- Difficult to make reactive agents that learn

- Since behavior emerges from component interactions plus environment, it is hard to see how to engineer specific agents (no principled methodology exists)

- It is hard to engineer agents with large numbers of behaviors (dynamics of interactions become too complex to understand)

Hybrid Architectures

Many researchers have argued that neither a completely deliberative nor completely reactive approach is suitable for building agents. They have suggested using hybrid systems, which attempt to marry classical and alternative approaches. An obvious approach is to build an agent out of two (or more) subsystems:

- a deliberative one, containing a symbolic world model, which develops plans and makes decisions in the way proposed by symbolic AI.

- a reactive one, which is capable of reacting to events without complex reasoning.

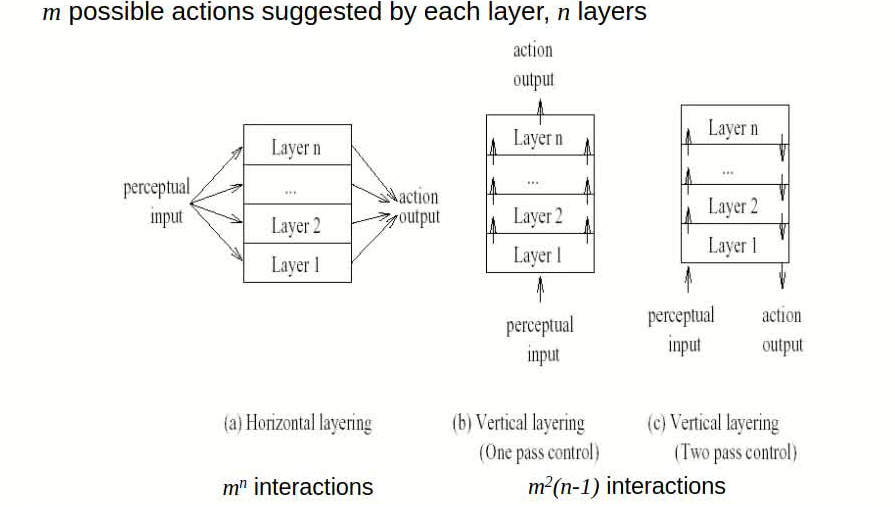

Often, the reactive component is given some kind of precedence over the deliberative one. This kind of structuring leads naturally to the idea of a layered architecture, of which TOURINGMACHINES and INTERRAP are examples. In such an architecture, an agent’s control subsystems are arranged into a hierarchy, with higher layers dealing with information at increasing levels of abstraction. A key problem in such architectures is what kind of control framework to embed the agent’s subsystems in, to manage the interactions between the various layers. Typically, the control frameworks are based on horizontal layering and vertical layering:

- Horizontal layering: Layers are each directly connected to the sensory input and action output. In effect, each layer itself acts like an agent, producing suggestions as to what action to perform.

- Vertical layering: Sensory input and action output are each dealt with by at most one layer each.

Related Posts / Websites 👇

📑 Ray - NTU SC4003 Lecture 3 Note: Intelligent Agent Prolegomenon

📑 Ray - NTU SC4003 Lecture 4 Note: Agent Decision Making

📑 Ray - NTU SC4003 Lecture 7 Note: Working Together Benevolent/Cooperative Agents

📑 Ray - NTU SC4003 Lecture 8 Note: Game Theory Foundations

📑 Ray - NTU SC4003 Lecture 9 Note: Allocating Scarce Resources: Auction

Comments