Working Together Benevolent/Cooperative Agents

In the previous related posts, we discussed how agents can make decisions and act in an environment. However, we often have multiple agents working together in a multi-agent system. In this chapter, we will discuss why and how agents work together. Since agents are autonomous, they have to make decisions at run-time, and be capable of dynamic coordination. This coordination requires agents to share tasks and information. But, if agents are designed by different individuals, they may not have common goals. Therefore, we need to make a distinction between benevolent agents and self-interested agents. In this chapter, we will focus on benevolent agents, which are agents that are designed to work together and achieve a common goal. This post discuss cooperative agents in Lecture 7 of the SC4003 course in NTU.

Benevolent agents are designed to help each other whenever asked, as our best interest is their best interest. This simplifies the system design task enormously, and in this post we first focus on cooperative distributed problem solving (CDPS).

However, in more general cases, agents may represent the interests of individuals or organisations, which cannot be assumed to be benevolent. Instead, agents will act to further their own interests, possibly at the expense of others, which may lead to conflicts (the so called self-interested agents). This greatly complicates the design task, and may require strategic behavior, such as reaching agreements and using game theory, which will be covered in the later posts.

There are basically two Criteria for assessing an agent-based system, coherence and cooperation. Coherence means that how well the multiagent system behaves as a unit along some dimension of evaluation , while Cooperation means the the degree to which the agents can avoid extraneous activity such as Synchronizing and aligning their activities.

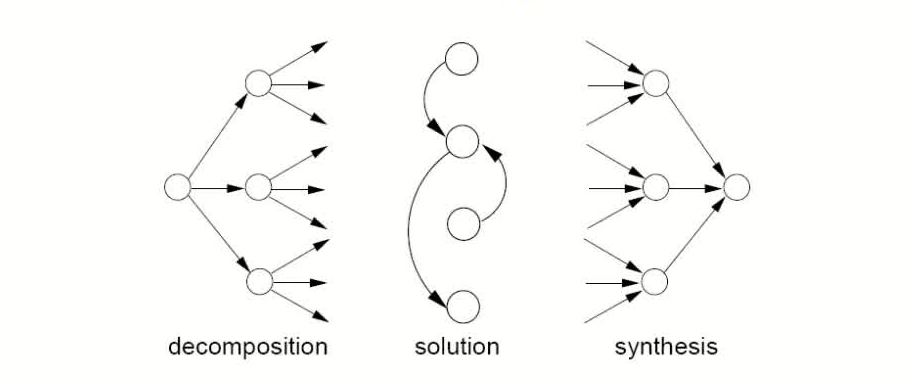

In the context of Cooperative distributed problem solving (CDPS), we mainly focus on the following three stages:

- Problem decomposition: The overall problem to be solved is divided into smaller sub-problems. Typically a recursive/hierarchical process, where subproblems get divided up also. The process will focus on how this is done and who does the division.

- Sub-problem solving: The sub-problems derived in the previous stage are solved. Agents typically share some information during this process. A given step may involve two agents synchronizing their actions.

- Answer synthesis: In this stage solutions to sub-problems are integrated. This may be hierarchical. Solutions in different abstract levels will be different.

Table of Contents

Task Sharing - The Contract Net

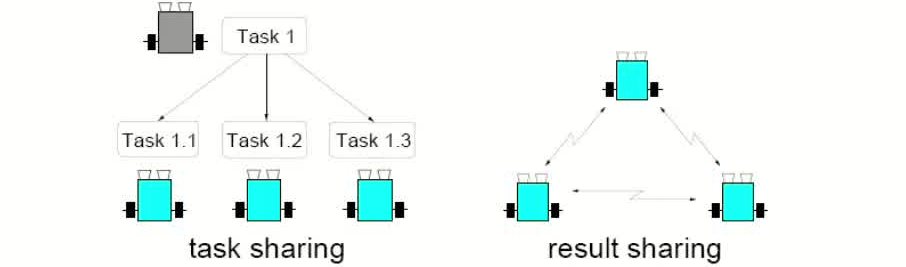

Given this model of cooperative problem solving, we have two activities that are likely to be present:

- task sharing: components of a task are distributed to component agents; how do we decide how to allocate tasks to agents?

- result sharing: information (partial results etc) is distributed; how do we assemble a complete solution from the parts?

Stages of Contract Net

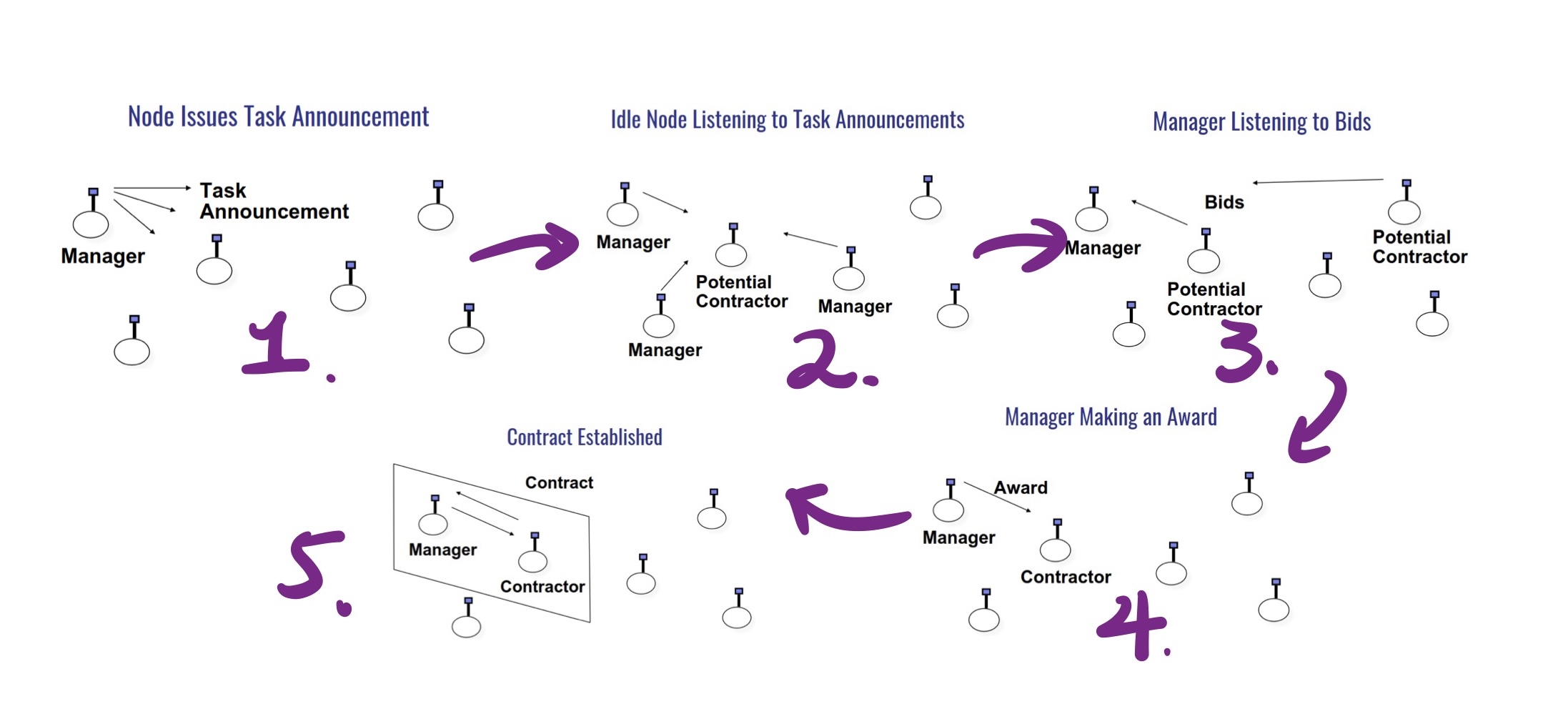

Well known task-sharing protocol for task allocation is the contract net, which includes five stages, Recognition, Announcement, Bidding, Awarding, and Expediting. Let’s have a look at each stage.

In stage of recognition, an agent recognises it has a problem it wants help with. Agent has a goal, and either realises it cannot achieve the goal in isolation since it does not have capability, or realises it would prefer not to achieve the goal in isolation (typically because of solution quality, deadline, etc). As a result, it needs to involve other agents.

During the announcement stage, the agent with the task sends out an announcement of the task which includes a specification of the task to be achieved. Specification must encode description of task itself, any constraints (e.g., deadlines, quality constraints), and meta-task information (e.g., “bids must be submitted by…”). The announcement is then broadcast.

Agents that receive the announcement decide for themselves whether they wish to bid for the task. The key factors are that they must decide whether it is capable of expediting task and determine quality constraints and price information. If they do choose to bid, then they submit a tender.

Agent that sent task announcement must choose between bids and decide who to award the contract to. The result of this process is communicated to agents that submitted a bid. The successful contractor then expedites the task. In some case, the process may involve generating further manager-contractor relationships: sub-contracting.

The collection of nodes is the contract net. Each node on the network can, at different times or for different tasks, be a manager or a contractor. When a node gets a composite task (or for any reason can’t solve its present task), it breaks it into subtasks (if possible) and announces them (acting as a manager), receives bids from potential contractors, then awards the job (example domain: network resource management, printers, ).

Issues for Implementing Contract Net

To effectively manage task allocation and execution, it is crucial to address several key aspects: specifying tasks clearly, defining the quality of service required, deciding on bidding strategies, selecting between competing offers, and differentiating offers based on multiple criteria. These considerations ensure a structured and efficient approach to task management in a multi-agent environment.

On the question how to bid. We say At time $t$ a contractor $i$ is scheduled to carry out combine task $T_i$. Contractor $i$ also has resources $e$. Then $i$ receives an announcement of task specification $ts$, which is for a set of tasks $T(ts)$. These will cost $i$ $c(T(ts))$ to carry out. The marginal cost of carrying out $T(ts)$ will be:

\[u(T(ts) | T_i) = c(T_i \cup T(ts)) – c(T_i)\]which is the difference between carrying out what it has already agreed to do and what it has already agreed plus the new tasks. Due to synergies, the marginal cost is often less than $c(T(ts))$. In fact, it can be zero — the additional tasks can be done for free. As long as $u(T(ts) | T_i) < e$ then the agent can afford to do the new work, then it is rational for the agent to bid for the work, otherwise not.

Result Sharing

In results sharing, agents provide each other with information as they work towards a solution. This collaboration leads to improved problem solving since independent pieces of a solution can be cross-checked, combining local views can achieve a better overall view, and shared results can improve the accuracy of results. Additionally, sharing results allows the use of parallel resources on a problem, which can accelerate the derivation of a solution.

Result Sharing in Blackboard Systems

A group of specialists are seated in a room with a large blackboard. They work as a team to brainstorm a solution to a problem, using the blackboard as the workplace for cooperatively developing the solution. The session begins when the problem specifications are written onto the blackboard. The specialists all watch the blackboard, looking for an opportunity to apply their expertise to the developing solution. When someone writes something on the blackboard that allows another specialist to apply their expertise, the second specialist records their contribution on the blackboard, hopefully enabling other specialists to then apply their expertise. This process of adding contributions to the blackboard continues until the problem has been solved.

The blackboard system represents the pioneering scheme for cooperative problem solving. It uses a shared data structure (BB) where multiple agents (KSs/KAs) can read and write. Agents contribute by writing partial solutions to the BB, which can be organized in a hierarchical manner. However, mutual exclusion is crucial over the BB to prevent conflicts, which can become a bottleneck due to the need for a lock mechanism, resulting in non-concurrent activity.

| Knowledge Source (KS) | Knowledge Agent (KA) | |

|---|---|---|

| Emphasis | Knowledge module | Active agent |

| Trigger | Passive, triggered by blackboard | Active, perceives and acts on new information |

| Autonomy | Low, knowledge is applied when triggered | High, more autonomous in perceiving and acting |

Result Sharing in Subscribe/Notify Pattern

Subscribe/Notify is a design pattern where objects register interest in specific events and are proactively notified when those events occur, enabling efficient and timely result sharing in dynamic systems. Rather than continuously polling other objects to check for changes, subscribers simply declare their interests once, and then rely on the system to alert them when relevant updates arise. This shift from pull-based to push-based communication significantly reduces unnecessary computational overhead and improves responsiveness, making it especially suitable for distributed, event-driven environments.

In this pattern, objects must maintain awareness of each other’s interests, typically by managing a subscription list that records which objects should be notified for each type of event. When a triggering event occurs, the publisher automatically notifies all relevant subscribers, allowing each subscriber to immediately act upon the new information without delay. As a result, information is proactively shared among objects, promoting real-time collaboration and more cohesive system behavior.

Within the context of cooperative agents and result sharing, the Subscribe/Notify pattern provides an elegant mechanism for synchronizing distributed knowledge contributions. Agents can specialize in different aspects of a problem, subscribe to updates relevant to their expertise, and progressively build a shared understanding without requiring centralized control or direct, constant querying. This fosters scalability, reduces communication complexity, and enhances the ability of multi-agent systems to solve complex problems collaboratively.

Handling Inconsistency

A group of agents may have inconsistencies in their beliefs or goals/intentions. Inconsistent beliefs arise because agents have different views of the world, which may be due to sensor faults or noise or just because they can’t see everything. Inconsistent goals may arise because agents are built by different people with different objectives. There are three classical ways to handle inconsistencies:

- Do not allow it: For example, in the contract net the only view that matters is that of the manager agent.

- Resolve inconsistency: Agents discuss the inconsistent information/goals until the inconsistency goes away (argumentation).

- Build systems that degrade gracefully in the face of inconsistency FA/C (Functionally accurate/cooperative).

In functionally accurate/cooperative (FA/C) systems, agents are specifically designed to handle incomplete, inconsistent, and outdated knowledge without requiring full synchronization. Instead of assuming that local knowledge bases must be complete and consistent at all times, agents solve problems opportunistically and incrementally, advancing solutions whenever possible based on partial information. This approach reduces computational overhead and makes systems far more robust in dynamic, uncertain environments.

Rather than exchanging raw data, agents in FA/C systems share high-level intermediate results, allowing them to collaboratively refine their understanding and correct inconsistencies implicitly through comparison and integration. Problem solving is not bound to a rigid sequence of steps; multiple alternative paths to a solution are allowed. If one path fails, agents can easily shift to another, ensuring that progress toward the goal continues. This decentralized, resilient problem-solving strategy enables cooperative agents to operate effectively even when global consistency is unattainable.

Coordination

Coordination is managing dependencies between agents. There are some examples in the real world:

- We both want to leave the room through the same door. we are walking such that we will arrive at the door at the same time. What do we do to ensure we can both get through the door?

- We both arrive at the copy room with a stack of paper to photocopy. Who gets to use the machine first?

Social Norms

The human society are often regulated by (often unwritten) rules of behavior. E.g. the rule when boads bus at stops, first come first board. In an agent system, we can design the norms and program agents to follow them, or let norms evolve.

Agents can be described as a function which, given a run ending in a state, gives us an action:

\[Ag : R_E \rightarrow Ac\]where $R_E$ is the set of all possible runs of agent $Ag$ in ending in a state $e \in E$, $Ac$ is the action space.

A constraint is then a pair:

\[\langle E', \alpha \rangle\]where $E’ \subseteq E$ and $\alpha \in Ac$. This constraint says that $\alpha$ cannot be done in any state in $E’$. A social law is a set of constraints

Joint Intentions

Joint intentions extend the idea of individual intentions to teams of agents, where agents form a collective commitment to achieving a goal (G), motivated by a shared reason (M). Levesque formalized this through the concept of a Joint Persistent Goal (JPG), where agents collectively maintain G until a termination condition is mutually believed.

Initially, agents believe that G is not yet achieved but remains possible. They continue working towards G until it becomes mutually believed that (1) G is satisfied, (2) G is impossible, or (3) the motivation M is no longer valid. If an agent individually discovers that a termination condition is met, it does not immediately abandon G. Instead, it adopts a new goal: to ensure that this knowledge becomes mutually believed among all agents through communication.

This process guarantees coordinated team behavior, ensuring agents only stop pursuing G when everyone is fully informed. Mutual belief via communication is essential to synchronizing agent actions and properly concluding joint activities.

Joint intentions require agents to persist toward a goal until mutual belief of goal achievement, impossibility, or demotivation is established, ensuring coordinated termination through communication.

Related Posts / Websites 👇

📑 Ray - NTU SC4003 Lecture 3 Note: Intelligent Agent Prolegomenon

📑 Ray - NTU SC4003 Lecture 4 Note: Agent Decision Making

📑 Ray - NTU SC4003 Lecture 5 Note: Agent Architecture

📑 Ray - NTU SC4003 Lecture 8 Note: Game Theory Foundations

📑 Ray - NTU SC4003 Lecture 9 Note: Allocating Scarce Resources: Auction

Comments